The new Mercury V-12 Verado 600 outboard draws attention, of course, for its jaw-dropping size. If the engine’s 12 cylinders, 7.6 liters, 1,260 pounds and 600 horsepower don’t impress, perhaps racking four of these majestic beauties across a transom might induce you to walk down the dock to take a look.

Mercury designed the Verado 600 to efficiently move the largest outboard-powered dayboats and center-consoles currently available, and even larger boats in the future. It seems that creating horsepower was the easy part of this project because the V-12 engine is essentially, if not exactly, the Mercury 4.6-liter V-8 with four additional cylinders.

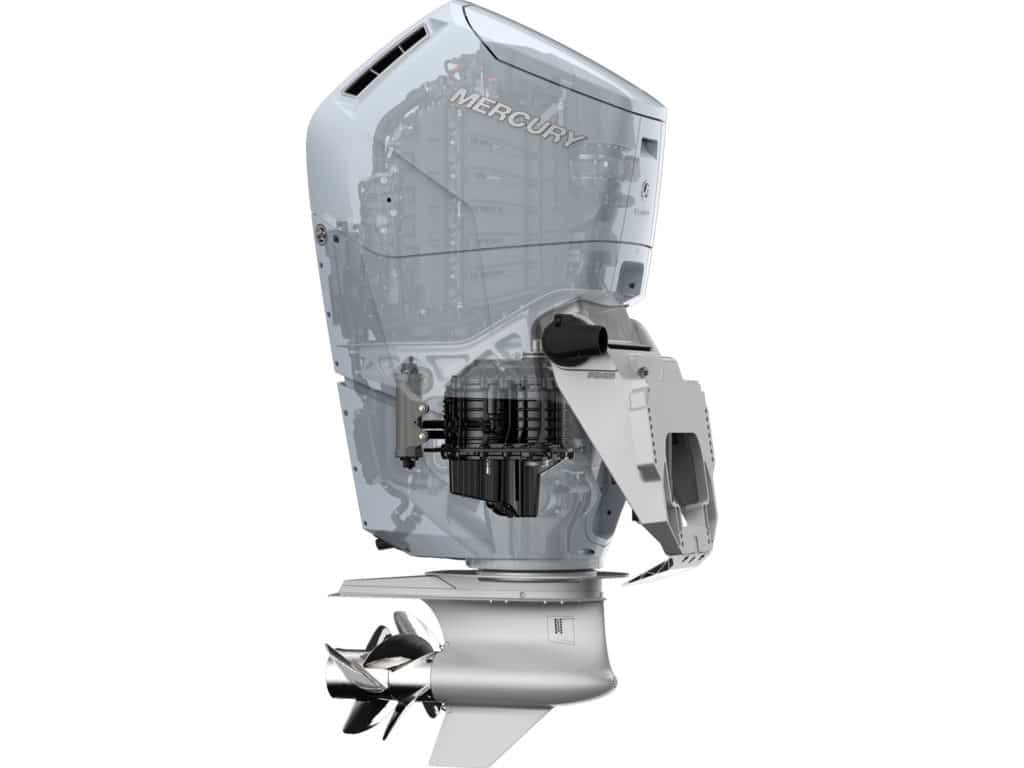

Two elements of technological magic that make the Verado 600 compelling lie below the powerhead. A two-speed automatic transmission amplifies torque and boosts economy, while a steerable gear case adds agility and keeps the transom spacing tight.

“Everything from the powerhead down is an invention,” says David Waldvogel, drive systems engineering manager at Mercury, part of a team that spent five years developing these patented designs, the first for any outboard.

Two-Speed Automatic

The two-speed automatic transmission located below the powerhead offers a number of benefits. Placing forward, neutral and reverse gears in the transmission keeps the gear case as small as possible (6 inches in diameter), for a significant reduction in drag. The engine’s smooth hydraulic shifting becomes especially apparent when operating in joystick mode.

The Verado 600 features dual contra-rotating propellers, with four blades on the lead prop and three blades following. The maximum prop diameter measures 18 1/4 inches—ideal blade area for lifting a heavy boat on plane and holding it there at lower cruising speeds.

But it takes a lot of muscle to turn those big props. A low gear ratio—think about your car starting in first gear—amplifies torque to give the engine more leverage on the propellers, for an effective hole shot with minimal bow rise. The gear ratios in the transmission, combined with a 1.75-to-1 ratio in the gear case, result in a very low 2.97-to-1 final ratio in first gear.

As the boat gains speed, the transmission automatically upshifts to the taller second gear, with a 2.5-to-1 ratio, which is 43 percent lower than that of a Verado 400, so engine power is still being amplified. This allows the Verado 600 to run props with a lot of pitch and to cruise at a much higher speed. For example, a Boston Whaler 420 Outrage with quad Verado 400 motors and 17-pitch props runs 32.5 mph at 4,500 rpm, while the same boat with triple Verado 600 motors and 31-pitch props runs 43.5 mph at 4,500 rpm. Both boats get 0.06 to 0.07 mpg fuel economy at that speed. More speed at the same rpm equals better economy.

The engine controller manages shifting based on torque demand. Similar to how an automobile shifts as it accelerates to pass, the Verado 600 will downshift in some situations, such as accelerating smartly from a slow cruise speed.

Novel Steering

Narrow engine spacing was a key design goal for the Verado 600 so the V-12 outboard could fit on the same transoms as V-8 and L6 Verado models. The Verado 600 features 27-inch center-to-center spacing, an inch wider than that of other Mercury models, but narrower than the 28.5 inches required for Yamaha XTO 425s or the 32-inch spacing between multiple Seven Marine 627 motors. Mercury accomplished this, in part, by keeping the powerhead stationary and steering only the gear case.

The gear case bolts to a hollow steering column extending into the midsection of the motor. A hydraulic rack-and-pinion steers it in response to a signal from the digital helm. This design eliminates all external steering hardware. Exhaust and cooling water routes through ring-shaped channels in the steering housing, which mate to channels in the gear case.

Because only the gear case steers, it can move up to 45 degrees port and starboard, compared with about 30 degrees each direction for a traditional outboard. This gives the V-12 more authority at low speeds and in joystick mode—which is essential to control large boats—without swinging those giant powerheads back and forth while docking. As boat speed increases, the steering range decreases electronically, as determined by the boatbuilder.

The transmission and steerable gear case combine to deliver key elements that enable the application of tremendous power from this refined, sophisticated outboard motor.

About the author: Charles Plueddeman has been writing about boats and marine propulsion since 1987. You might spot him on Big Green Lake at the wheel of a 1951 Dunphy.