“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

— Søren Kierkegaard

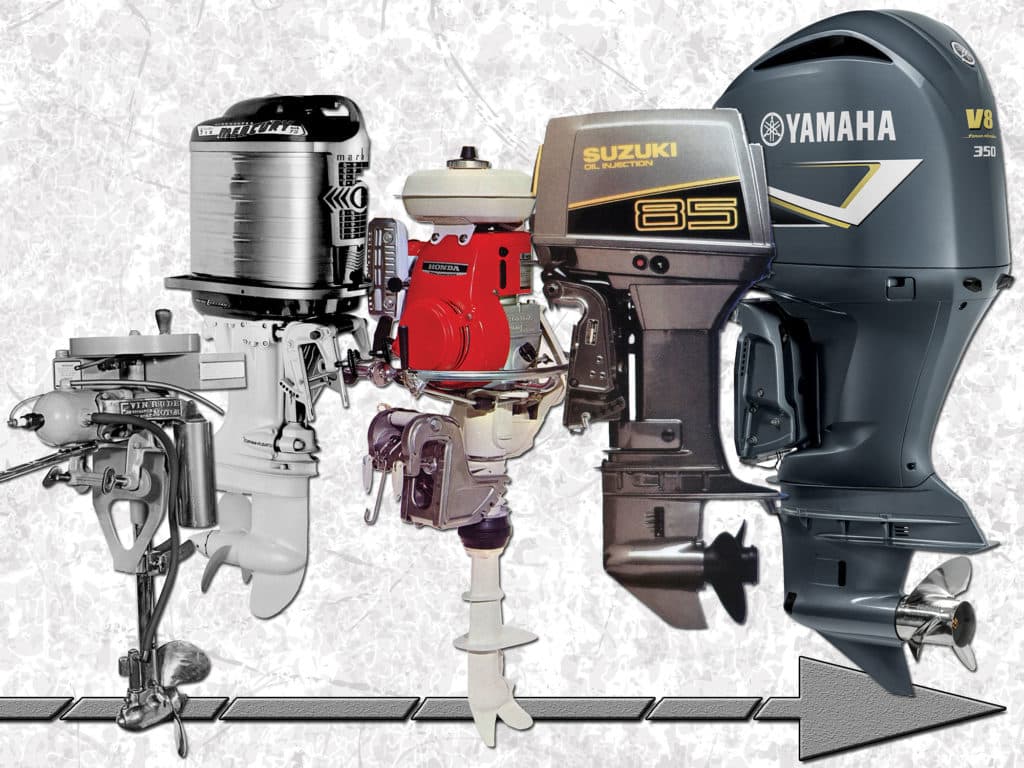

Turns out that life is similar to an outboard engine. Only when we look all the way back to this past century’s turn can we really understand how far we’ve come with today’s digital integration, computer-controlled internal-combustion technology and superior power-to-weight ratios.

You don’t have to be an engineer to grasp the basics. Of course it helps if you have a little curiosity and fascination. That’s likely what skilled Wisconsin machinist Ole Evinrude had when he created the first commercially viable Detachable Row Boat Motor in 1909. That 1.5 horsepower, single-cylinder motor worked off dry-cell batteries. Ole cranked it by hand to start, rotating a knobbed flywheel.

In the 108 years since, many outboard-engine companies have come and gone. In 1947, for instance, 14 other outboard makers competed with Evinrude in the United States, the company says. But Evinrude and four other major manufacturers — Mercury (1939), Honda (1964), Suzuki (1977) and Yamaha (1983) — eventually emerged in this country, pushing each other to innovate and dominate the American marine market.

1909: Ole Evinrude’s World

While all early outboard engines could be classified as two-strokes, all current Evinrude E-TECs are also two-strokes. The company has chosen to redefine two-stroke technology rather than switch to four-stroke design.

Two-strokes traditionally offered lightweight power, but the older models also lacked fuel efficiency and discharged environmentally damaging smoke and oil. The basic difference between two- and four-stroke engines: A two-stroke completes its cycle with only two movements (one up, one down) of the piston during one crankshaft revolution; a four-stroke requires four piston movements during two crankshaft revolutions to complete a power cycle.

With the current E-TEC G2 two-stroke technology, however, Evinrude vastly improved on the original concept. But that didn’t happen overnight.

Through the mid-1950s, Evinrude and others struggled to develop outboards that topped 100 hp. In 1956, Mercury’s Mark 75 — the first six-cylinder engine — managed only 60 hp. Even so, in 1960, Evinrude’s four-cylinder Starflite II set a speed record of 114.65 mph. The company followed that innovation with push-button electric shift.

Bigger and Faster Outboards

In 1975, the first V-6 outboard engines — Evinrude’s 200 and Mercury’s 175 — finally scaled the 100 hp barrier. “There were certainly big sterndrives and inboard engines before then,” says Jason Eckman, Evinrude global product manager. “But if you wanted an outboard, you were stuck at a lower horsepower.”

Greater horsepower paved the way for larger outboard-powered vessels, jump-starting the era of recreational boating and fishing for a more diverse cross section of Americans.

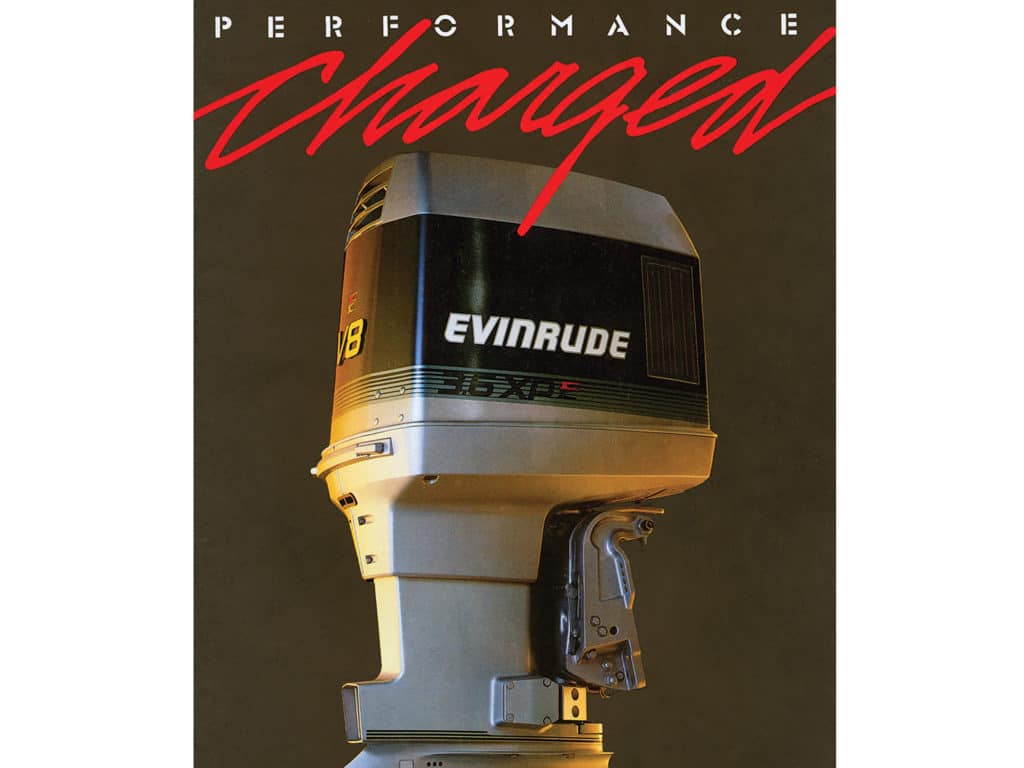

Leaps and bounds occurred during the 1980s and ’90s, first with the advent of electronic fuel injection, and in 1996 with direct fuel injection from Evinrude’s Ficht technology and Mercury’s Orbital DFI. At the same time, the Environmental Protection Agency released its emissions standards for outboards and designated a phase-in regulatory approach.

Evinrude E-TEC Designs

But in 2000, Evinrude’s parent, Outboard Marine Corporation, filed for bankruptcy. Bombardier, a Canadian transportation and aerospace company, bought the assets and rolled out Bombardier Recreational Products outboards in 2001.

“Mostly, carbureted two-strokes had to be replaced,” Eckman says. “Some companies chose to go to four-strokes rather than innovate with two-strokes, but we already had expertise in two-strokes with snowmobiles. Our customer prefers the two-stroke’s power-to-weight ratio and added midrange torque. It made sense to continue to invest in that technology, to meet and eventually exceed the EPA requirements without taking away that torque and fuel economy.”

In 2003, Evinrude launched E-TEC, the next generation of two-stroke, direct-fuel-injection technology with the same block as previous two-strokes but with a new cylinder head designed to accept the fuel injector. “With direct injection, we can change the timing of the fuel injection. During idle, you don’t need the cylinder to be completely full of fuel and air; you need only a little. By injecting fuel directly into the cylinder, we can be more precise.”

Second Generation Evinrude E-TECs

Evinrude continued to enhance its technology and drive larger E-TEC outboards to market. The company even won an EPA award in 2005 for its emissions control.

In 2014, the company launched its second generation of E-TEC outboards, the G2s — “the first time BRP has designed an engine block from scratch to be optimized around direct injection,” Eckman says.

“The main thing was to perfect the combustion by optimizing the air flow. The way the air and fuel mix inside the cylinder to get a perfect ratio, and then the timing of the exhaust so no fuel escapes: It’s almost like a musical instrument.”

The G2 stands out in multiple ways. BRP integrated power steering into the engine to offer a better piloting experience, and (though the concept had been done before) the company mounted the oil reservoir inside the cowling to save space. BRP also added iTrim, a system that automatically trims the outboard based on load and rpm, and customizable color panels to match the engine with the hull.

1939: Mercury Moments

Although Mercury Marine introduced its first outboards in 1939, it wasn’t long before the company also dominated the sterndrive market. That side-by-side development gave Mercury expanded capabilities.

The 1950s

After its first six-cylinder outboard debuted in 1956 (an in-line-six known fondly as the Tower of Power), Mercury followed in 1975 with one of the first V-6 outboards: the 2L 175 hp Black Max Merc 1750, which company founder Carl Kiekhaefer called “the meanest, toughest, most beautiful machine we’ve ever built.”

The Mercury Black Max

The Black Max used power porting, a piston design that provided an additional source of fuel and air that increased horsepower without additional new parts.

Direct Fuel Injection

Mercury delivered the first recreational electronic fuel injection in 1987 in its V-6 220 XRi. EFI also ushered in the first electronic-control modules — essentially a computer brain — to outboards.

In 1996, Mercury continued its two-stroke evolution with the direct-injection OptiMax. The DFI technology helped Mercury meet the new EPA emissions requirements. OptiMax featured a unique air-assist injection system that employed an air compressor and a lower-pressure fuel injector rather than a high-pressure liquid pump, says David Foulkes, Mercury’s head of product development and engineering.

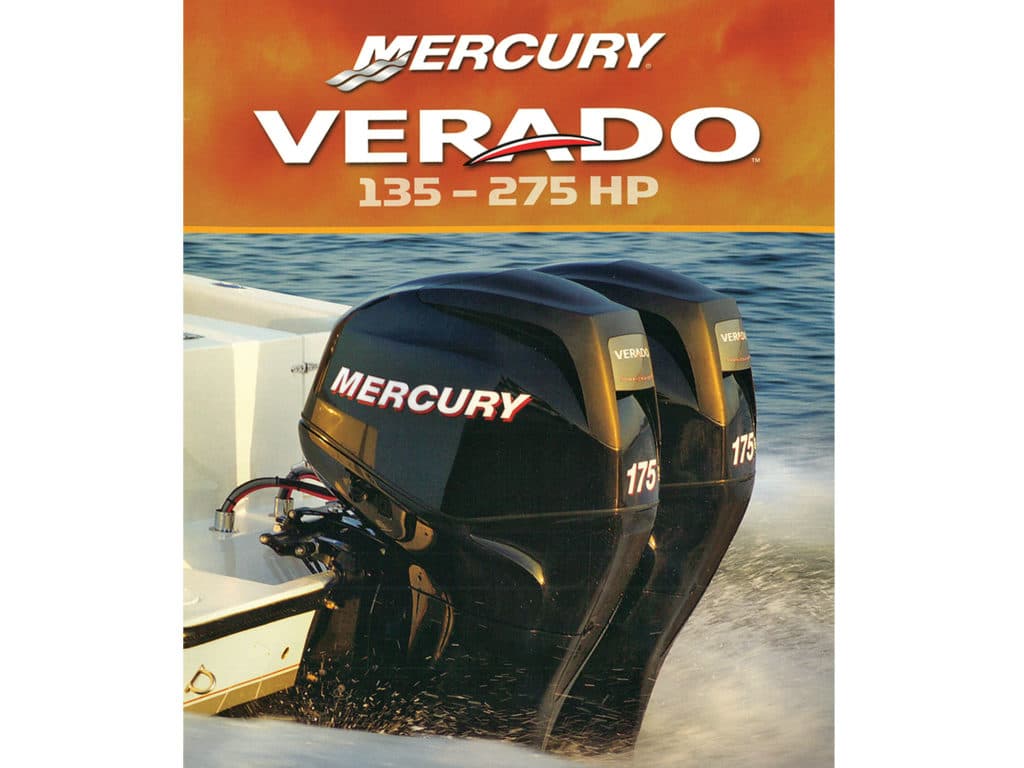

Supercharged Mercury Verados

Optis mixed compressed air with fuel, blasting it into the combustion chamber. The fine fuel atomization achieved with that system allows OptiMax engines to burn diesel and jet fuel as well as gasoline, Foulkes says.

As conventional two-strokes began to raise emissions red flags at the EPA in the 1990s, companies such as Honda and Yamaha rolled out 100-plus-horsepower four-strokes (1998). Mercury introduced its Verado platform in 2004 with a complete line of higher-horsepower, supercharged four-stroke outboards designed to target the two-stroke market with equivalent power and torque features.

Mercury Outboard Tech Advances

Supercharging allows Mercury to reduce the displacement (2.6L for Verado 200 to 400 hp) and therefore the weight of the outboard. In the past decade, Mercury has completed its full four-stroke product line all the way up to the Racing 400 Verado.

In addition, Foulkes notes that larger Verados, which use in-line-six powerheads, are narrow engines that fit on 26-inch centers. That allows large-center-console builders to pile as many as five outboards on a transom.

Along the way, Mercury has also developed several new materials such as its proprietary anticorrosive alloys as well as some unique systems like Advance Midsection (AMS) on Verados. AMS reduces the transmission of engine vibration to the boat by cradling the engine around its midsection.

(See the most-recent updates to Mercury’s outboard family here.

Digital Details

Mercury has also instituted Joystick Piloting, Active Trim, Vessel View (now with digital gauge display as well as sonar and chart plotting) and a new steering helm using Magneto Realogic Fluid, which contains suspended particles that provide greater resistance with electrical current. Boaters can effectively set their own resistance and suspension, like stiffening the shocks on a car.

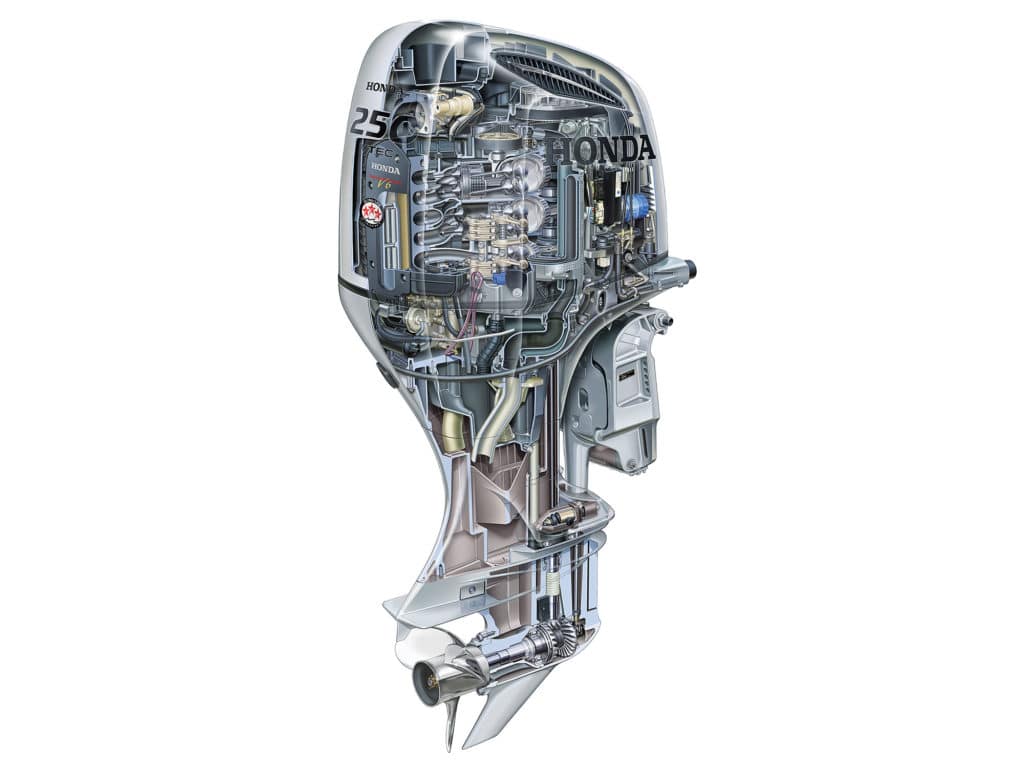

1967: Honda, All Four-Strokes

Contrary to Evinrude and its focus on two-strokes, Honda Marine has always concentrated on four-stroke technology for outboards. Four-strokes, of course, are the dominant power for automobiles, a primary interest for the overall Honda Motor Co. But the belief in four-strokes goes deeper than just an understanding and expertise with the design.

“Mr. Honda saw two-strokes spouting smoke and oil into the atmosphere and water. He started pioneering on the four-stroke side to keep the planet cleaner,” says Dennis Ashley, senior OEM sales manager.

Honda introduced its four‑stroke outboards to the United States in 1967, with the GB25 and GB40. But higher-horsepower four-strokes took a while to develop; not until 1998 did Honda surpass the 100 hp mark with its 130. That engine also featured electronic fuel injection and Honda’s first ECM.

That same year, four-stroke Hondas became the first outboards to meet the EPA’s more-stringent 2006 emissions standards, Ashley says.

Honda VTEC Origins

As boaters began accepting four-strokes, Honda took the spotlight in 2001 with its BF225. (Yamaha introduced a similar 225 the same year.) Key to that larger four-stroke was Honda’s industry-first Variable Valve Timing and Lift Electronic Control, a trickle-down technology from the car industry, Ashley says.

“VTEC changes the lift and duration of the valves opening and closing. The lift is how high the valve opens to let in extra air and fuel, and the duration is the amount of time it stays open,” he says. “Everyone can change where the air and fuel comes in, but no one else can change the lift and duration while the engine’s running.”

Other outboard-engine builders employ variable valve timing but use a cam phaser to make the adjustments, Ashley explains. The process improves drivability at low rpm, “but will not maximize the ability of the engine when high rpm is necessary.”

VTEC is “kind of like having two cam shafts in your car, one for low-speed operation and one for high rpm power,” he adds.

Sensor Technology

During the past 16 years, Honda has expanded its range to the BF250 (2011), and introduced a series of technologies made possible with an ever‑evolving electronic-control module. Honda’s current ECM measures about 3-by-5 inches and is about an inch and a half thick. It features data ports for input and output. Sensors placed throughout the engine deliver measurements and data to the module.

Honda’s BLAST technology — which generates low-end acceleration for pushing the boat over on plane — depends on the ECM to sense the engine’s load. When the helmsman buries the throttle, BLAST adjusts the timing, creating the most horsepower for that demand.

Fly by Wire

Also during this past decade, intelligent shift and throttle — also called digital throttle and shift or fly-by-wire — removed the cables that revved the engine and replaced them with electrical servos, Ashley says. “A lot of people might cringe about that, but it has been the standard in the automobile industry,” he says. “Once upon a time, the gas pedal had a metal rod that attached to the top of the engine. The gas pedal today is a potentiometer, an electrical signal travels through a wire and opens and closes the valve.”

Digital throttling enables troll modes and intelligent rpm synchronization. It also ushered in automatic trim controls and other enhancements at the helm.

Honda also employs Lean Burn Control, which senses the boat’s load at any given time (using an oxygen sensor in the exhaust) and makes the fuel/air mixture leaner or richer, depending on need. Three-Way Cooling allows water to stay in the block longer by using three separate thermostats to route water where it’s needed.

1977: Suzuki Systems

Suzuki outboards debuted on the U.S. market in 1977, and the company was first to introduce automatic oil injection in 1980 in a three-cylinder 85 hp DT85 engine. Prior to that time, boaters had to pre-mix oil with gasoline.

Suzuki 1990s Transition

Suzuki also transitioned to producing four-stroke outboards in the late 1990s as EPA emissions rules evolved and boaters began to embrace the technology. But it wasn’t until the early 2000s that the company’s larger four-strokes emerged, with the DF140 in 2002.

Accelerating Improvements

In 2004, Suzuki and Yamaha both debuted 250 hp V-6 four-strokes. (Mercury’s 250 Verado featured an in-line-six design.)

“One of the things we do on all our motors, we offset the drive shaft,” says Dean Corbisier, Suzuki event manager. “That moves the powerhead forward on the downhousing so more weight is moving the boat. It gives us a really low gear ratio at the lower unit.”

Selective Rotation

Suzuki also pioneered Selective Rotation in outboards in 2011. A controller under the cowling allows a dealer to change the direction the propeller spins. Previously, dealers had to stock different motors with different lower units — some would spin the prop clockwise, while the others spun it counterclockwise. On multiple-outboard installations, one or more props must spin clockwise while the others move counterclockwise to offset directional torque. (Read about Suzuki’s latest introduction — a 350 hp outboard.)

1983: Yamaha Focus

While Yamaha outboards came to the U.S. market in 1983, the company began operating in 1948 in Japan, initially building motorcycles and other motorized gear. Today, Yamaha can claim two of every three outboard engines in the saltwater market.

Why? Yamaha believes the company sets itself apart by staying high-tech. Yamaha also pursued partnerships with boatbuilders, elevating its visibility. And finally, customer confidence comes down to proven dependability, power, performance and reputation, the company says.

Out of the box, Yamaha’s first U.S. outboards (two-strokes) featured Precision Blend Oil Injection, which worked off the engine load and speed, says David Meeler, Yamaha product planning and information manager. Under lighter loads, the system added less oil than during times of higher rpm and loads.

Two-Stroke Time

Soon afterward, Yamaha began introducing small four-strokes, and eventually broke the 100 hp barrier in 1998 with its 100. On the two-stroke side, Yamaha HPDI (high pressure direct injection) emission-certified outboards debuted in 1997, gaining quick success, particularly among bass‑boat owners.

Two-Stroke to Four-Stroke

However, Yamaha saw the four-stroke writing on the wall, and just three years later the company led again (along with Honda) in producing V-6 four‑stroke 200s and 225s. “Nobody believed the four-stroke would ever give up 200 hp, much less 225,” Meeler says. “One way, we were able to with in-bank exhaust. We reversed the exhaust so it comes out in the center of the bank and the intake comes in from the outside. It increased the power of the engine with a more direct flow of air.

“We used some different ways of looking at the same thing. We realized that an engine is just a giant air pump. We made it easy for the engine to breathe by using a more direct intake and exhaust path and four valves per cylinder.”

The V-6 F250 followed in 2004, bringing with it VCT, or variable camshaft timing.

“VCT allows the engine to take that deep breath sooner,” Meeler says. “If the operator asks for a burst in performance and the engine is turning slowly, the engine-control module will use engine oil to hydraulically move the intake camshaft, so the lobes will come around sooner and allow those valves to open quicker.”

Yamaha: Growing the Outboard Industry

Yamaha’s V-8 5.3L F350 created industry buzz in 2007. The 350, which Yamaha says was developed with 10 key boatbuilders, also came with fly-by-wire controls. The F350 allowed manufacturers to build even larger center consoles; they could also create luxury express boats and give them outboard power.

Variable Camshaft Timing

In 2010, VMAX SHO (super‑high output) 200, 225 and 250 hp outboards debuted, combining the attributes of two-strokes with the smooth, quiet operation of four-strokes. Meeler says VCT is a big part of what gives the SHO its kick.

At the same time, Yamaha used plasma-fusion technology to melt pounds off the original F250. The process uses a metallic powder made from several alloys and takes a plasma arc to it at 13,000 degrees. The material instantly melts and fuses to the cylinder walls, creating a thin, slick surface that greatly outperforms steel cylinder sleeves.

“We’re continually tinkering with the efficiencies of the four different cycles of a four-stroke, along with weight, size and a host of other factors. Those four cycles are intake, compression, power and exhaust,” Meeler says. “Our goal is always to increase power, make the engine lighter, and give it better fuel economy.”

(Editor’s note: Since the first version of this article was written, Yamaha has debuted a new flagship outboard — the 425 XTO Offshore).

Future for Outboards

As we’ve seen in the past five or six years, outboard customization has outpaced technological changes within the engines themselves. Joystick steering, digital integration of gauges with ships’ systems and marine electronics, Bluetooth and Wi-Fi controllers, multicolor cowlings, purpose-built propellers, auto-trim systems — all have delivered fingertip control and immediate feedback to boaters.

Outboard companies told me they expect customization to continue, and they’ll also push for improved fuel economy. Alternative fuels are still a big question mark, and ethanol issues persist. Research is underway to find better protection for outboards and fuel systems from higher levels of ethanol, but no one would share any plans.

In the end, all marine companies strive to make boating as easy and fun as humanly possible. Outboard builders are certainly doing their part.