OASIS IN BLUE WATER

Blue water fishermen view a line or mat of Sargassum as an oasis for fish in the vast sameness of the open ocean. Seasoned offshore fishermen know that dolphin love Sargassum, the floating brown macroalgae that occur in warm and temperate oceans throughout the world. Dolphinfish can be found in schools numbering in the hundreds in the shadows of the floating mats.

These masses of algae teem with life. Schools of juvenile fish, such as filefish, jacks, flying fish, ballyhoo, and even billfish, tuna and dolphin swim among the dangling forest, seeking shelter from the many predators that search the shadows for their next meal. Among the interwoven branches many species of crabs, shrimp, pipe fish and seahorses make their home, riding the drifting vegetation as it is carried by the ocean’s currents. Each floating mat can be viewed as a mobile nursery. With the shelter it offers small animals to avoid predators and the great abundance of life that serves as a banquet table, it is easy to understand the nature of its attraction for marine life.

While fishermen as well as scientists recognize the attraction the Sargassum community offers dolphin, science has not documented the importance of this ocean plant to the occurrence of dolphin. The Dolphinfish Research Program (DRP) has collected information on the presence or absence of Sargassum in the capture of each fish tagged from 2006 through 2015, in an attempt to shed light on this plant’s role in the occurrence of dolphin. Over the past ten years this information has been collected on the 15,949 dolphinfish that have been tagged. These fish were tagged off the U.S. Atlantic Coast, Bahamas, Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico.

The net results showed that 10,547 fish were caught,547 fish were caught with Sargassum in the area (66 percent of all fish tagged), while 4,379 fish (27 percent) were caught in waters where it was absent. There were an additional 1,023 fish tagged where no information on Sargassum was provided. Discounting the unknown records, more than twice as many dolphin were caught where Sargassum occurred than in open water or around flotsam. Mass taggings of 40 or more fish in a single school did take place in open water, but more commonly in areas where Sargassum was present.

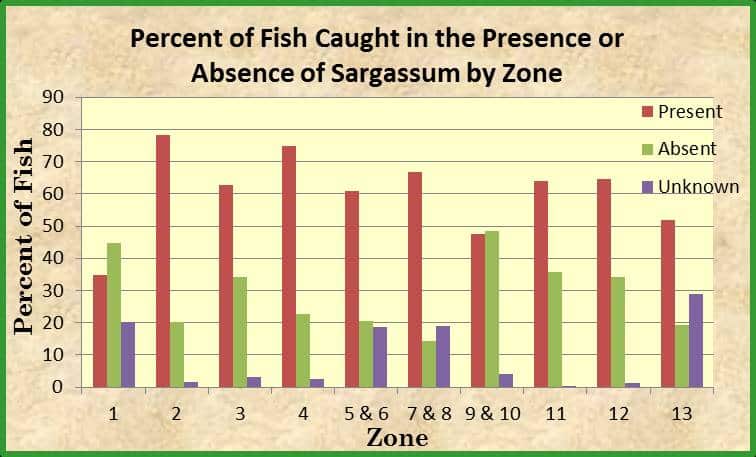

Information from different regions suggests that there could be variations in the percent of dolphin caught in association with Sargassum.

Tagging reports from the Bahamas, zone 1, and the Mid-Atlantic Bight, zones 9 and 10, indicated that more fish were caught in areas where Sargassum was absent. The Caribbean Sea also shows a high level of fish caught in open water, especially if the unknown records are considered with the absent records.

The Florida Straits, Key West to Key Largo, zone 2, exhibits the strongest association of dolphin with Sargassum, 78 percent of fish tagged. Surprisingly, the next region downstream, south Florida, Key Largo to Jupiter Inlet, zone 3, had an association level of just 63 percent of the fish being caught near Sargassum.

Then in the next region downstream of south Florida, the mid- Florida Atlantic coast, Jupiter Inlet to St. Augustine, the level of fish caught in the presence of Sargassum rose to 75 percent, near the level shown in the Florida Keys. This fluctuation of dolphin being found around Sargassum could be related to how the Florida current transports the oceanic weed from the Keys to this area. Those could be moving Sargassum farther to the east, and fishermen fishing the Miami to West Palm area tend to fish closer to shore than their counterparts along the mid-coast of Florida.

Anglers from St. Augustine, Florida, through South Carolina, zones 5 and 6, relied heavily on Sargassum, catching 61 percent of their fish around the floating weed. This is almost three times as many fish as they reported from open water, 21 percent. North Carolina fishermen reported that they caught more than four times more dolphin near Sargassum, 67 percent of the fish they tagged, than in areas where the weed was absent, 14 percent.

It should be noted that these two regions had some of the highest levels of tagging where no information was provided about Sargassum, 19 percent.

Mid-Atlantic Bight anglers, from Virginia through Massachusetts, zones 9 and 10, reported catching almost equal numbers of dolphin in areas where the weed was present as in areas lacking the grass. Dolphin were commonly reported being captured around commercial trap floats.

In the Gulf of Mexico, fishermen reported catching 64 percent of their fish in the presence of Sargassum, with 36 percent of the fish tagged being found in areas void of the floating algae. In the western North Atlantic waters bordering the northern and eastern islands of the Caribbean Sea, anglers caught 65 percent of the fish they tagged in areas with Sargassum and 34 percent of the fish where the weed was absent, levels similar to the Gulf.

Fishermen in the Caribbean Sea reported a slightly different story, indicating that 52 percent of their fish were found in areas with Sargassum, and only 19 percent of the fish came from areas where it was absent. However, these anglers failed to indicate the presence or absence of the weed in 29 percent of the tagging records. If this was their way of saying there was no Sargassum, then there would be a near-even split between dolphin being caught with or without the presence of grass.

The amount of Sargassum present in offshore waters off every region is highly variable not just year to year but from area to area in the same year. The Florida current, which runs from Key West to Cape Hatteras, or Gulf Stream as it is commonly called, begins to spread out and slow down as it passes the northern tip of the Bahamas Bank off Ft. Pierce. With this major change in its flow pattern, subtle variations within the current and the prevailing winds can have significant impact on whether the grass moves along the western side of the current where recreational fishermen are able to access it, or it moves to the east side of the Stream beyond reach of most recreational anglers.

Subsequently, the farther north the current travels from Ft. Pierce, the larger the area that the weed lines have to spread out over. This could explain some of the variations in the amount of Sargassum found from one region to the next in a single year.

Looking at Sargassum’s importance of to the catch of dolphin along the U.S. Atlantic coast in five-year periods, we can see a change in the importance of Sargassum in the dolphin catch during the period studied. The first graph below shows the portion of the dolphin tagged in each East Coast zone from 2006 through 2010. While every year showed a wide variability from zone to zone, the overall average proportion of the fish tagged that were caught in association with Sargassum was 59.93 percent.

When the zonal averages for fish caught in the presence of the oceanic weed off the East Coast are plotted out for the period 2011 through 2015, shown in the following graph, there is a noticeable change. During this more recent five-year period, the proportion of fish associated with the macroalgae rose to 71.63 percent of the fish tagged. Surprisingly, the increased catch associated with the grass did not carry into the Mid-Atlantic Bight. When that region is removed from the calculation, the proportion of fish caught in areas with the weed rose to 76.49 percent.

This change in the proportion of the fish caught for tagging associated with Sargassum brings up the question of whether there was an increase in the amount of Sargassum or an increase in the number of fish? The period of 2006 through 2010 saw 8,234 fish tagged, while from 2011 through 2015 a total of 7,715 fish were tagged. This is a decline of almost seven percent. Similarly, the National Marine Fisheries Service’s recreational harvest data showed that more than one million more dolphin were caught between 2006 to 2010, than from 2011 through 2015. So there wasn’t a greater abundance of fish in the later period. This would suggest that there may have been more Sargassum present.

The Gulf Coast Research Lab as well as several other research institutions reported that during 2011, massive quantities of pelagic Sargassum occurred throughout the Caribbean, and that a similar event occurred in 2014 and continued through 2015. Understanding that these large masses of Sargassum are transported from area to area by the ocean currents, then it is reasonable to expect that at least some of the macroalgae from the Caribbean would pass along the U.S. East Coast.

The major Caribbean ocean current moves from the southeastern Caribbean to the Yucatan Strait in the northwestern corner. Here the Caribbean current serves as the feeder to the Gulf of Mexico’s Loop current which ultimately supplies the energy for the Florida current off the Dry Tortugas below Key West, Florida. Then it is actually the Florida current that travels north along the South Atlantic Bight to Cape Hatteras where its name changes to the Gulf Stream. Knowing the connectivity of these currents, provides us an understanding of the pathway for Sargassum and dolphinfish in the Caribbean Sea to reach the U.S. Gulf and Atlantic coasts.

The previous figure depicted the years of 2011, 2014 and 2015 as having higher levels of dolphin associating with Sargassum in the South Atlantic Bight but the annual harvest estimates reported by the National Marine Fisheries Service showed anglers to have harvested on average fewer fish in these years than in the period 2006 through 2010. The takeaway here would be that an increase in the amount of Sargassum that the ocean’s constantly moving conveyor system may deliver to the East Coast does not necessarily mean that more dolphin will come with it.

One oddity that stands out in the last figure is likely rooted in changing current patterns. A consistent decline is shown in the percent of fish caught in association with Sargassum in the Mid-Atlantic Bight during the years when there was a super-abundance of grass in the Caribbean. It appears that while there was an increased abundance of grass in the South Atlantic Bight, it was not delivered to the Mid-Atlantic Bight within range of the area’s recreational fishermen.

Dolphin have been documented caught every month of the year off South Carolina. However, during the winter months they are normally six to fifteen pounds in size with an occasional 20-pounder. Bulls like this one just are not found off South Carolina at this time of year. Dolphin have been reported being caught in water as cold as 66 oF off the Palmetto State. Mr. Cone reported that his recorder indicated a water temperature of 70oF. This brute is just another example showing the nomadic nature of these great game fish.

About the Dolphinfish Research Program The only major effort dedicated to learning more about the movements and occurrence of dolphinfish in time and space, the Dolphinfish Research Program of Don Hammond focuses on the Gulf of Mexico, western North Atlantic and Caribbean Sea. The program also fosters more research into the biology and behavior of this fabulous game fish. It is privately funded, and benefits heavily from grants from the Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation, as well as the Hilton Head Reef Foundation, Grady-White Boats, AFTCO and others.