Warm, cobalt currents pushed hard over the Azores Bank, where massive schools of chub mackerel (what we call slimy-mackerel in Australia) were holding down deep. All hands dropped weighted sabikis; the baitwell soon brimmed with the large, lively baits.

Capt. Zak Conde called from the bridge to his young mate, Andrew Kennedy, to quickly bridle-rig a couple of mackerel and get them into the bait tubes bubbling with seawater.

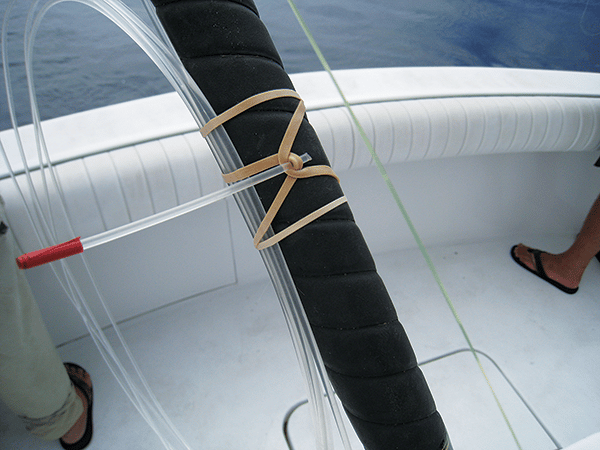

Each rig consisted of a circle hook attached to a 25-foot, 500-pound monofilament trace, carefully coiled and rubber-banded neatly to a stand-up 50-pound or 80-pound chair rod. A short length of plastic tube secured each end of the band, and needed only a quick pull for release and deployment of the bait. The size of the marlin raised would dictate the appropriate tackle selected.

That ability to instantly match tackle to fish is one of the beautiful things about switch-baiting, especially in these Atlantic waters, where the first fish could be a modest 300-pounder, and the next a true monster. Thoughts of the many granders hooked here crossed my mind as we set the spread of artificial lures in motion. Off the outriggers, we ran long two large, hard-body lures rigged with single Bristow hooks and two 12-inch, hookless softheads deployed via electric teaser reels at the bridge.

The lines off the teaser reels ran through fixed rings in the middle of the outrigger poles; we positioned teasers in close on the second and third waves. A mixed pattern like this targets multiple species and, as a rule, smaller blue marlin as well as whites tend to attack the longer (more distant) lures, whereas the larger marlin don’t mind the short (closer) ones. It’s the wash from the hull that sucks in the big mothers; it’s surprising how close they’ll come in to have a crack at a teaser.

Marlin at the Transom

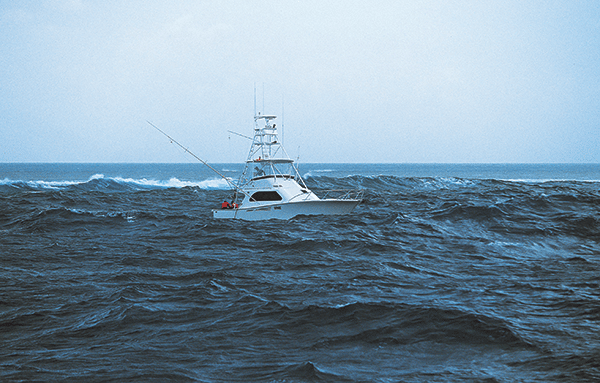

In the calm conditions that morning, the 8½-knot trolling speed worked perfectly for that spread. The wake from the 31-foot Black Watch Boca Raton was surprisingly clean. Suddenly, a quick strike from a white marlin popped the clip on the right long rigger, making the reel rattle momentarily. That woke us up, but the anticipation for something larger had us on edge when a solid blue around 700 pounds flashed into the spread and wacked the long teaser. Conde was quick to react with excited instructions as he slowly pulled the teaser to bring the beast toward the boat. At the same time, he slowed the vessel’s speed. The marlin kept coming.

Then the big girl nailed the softhead lure again, stretching the line on the teaser reel to the point of stopping its retrieve. Our angler, Thomas Peterson, decided to bait the fish on 80 and, like clockwork, the live bait was in the water by the time both teasers were almost to the boat. The angry marlin, now a mere 20 feet off the transom, wolfed down the bait down as if it were her last meal. Then she stayed there momentarily, seeming to gaze at the teaser, which was now dangling out of the water off the outrigger. It was an amazing sight to watch her turn away and start feeling the drag; that’s when all hell broke loose.

The crew reacted like a well-oiled machine. Kennedy quickly cleared the deck as Conde put on a show of boat-handling skills honed over decades of chasing blue marlin. (That ability is part of the reason Conde won the prestigious Billfish Foundation’s award for Top Release Captain in the Atlantic last year for releasing more than 320 blue marlin in one season.) The twin screws on the nimble Black Watch spun us around, and the chase was on. The big blue ran out 700 yards of line on her first blistering run before she started jumping and tail-walking.

Some time later, as the gap had shortened on the line, Conde spun the boat again and backed down hard, trying for a quick tag shot. The big blue, however, had other ideas. The reel screamed again as she headed for the depths, truly testing the 80-pound tackle. Peterson increased the drag pressure dramatically when the marlin slowed and started plugging (sulking deep) stubbornly.

What appeared to be an iffy -situation quickly changed as Conde maneuvered the boat to change the angle and direction on the line. The confused marlin started coming up, and left the water like a scud missile only 50 yards away, making two magnificent jumps. Conde saw his chance and backed down quickly for the tag shot on the fish of a lifetime.

Teaser Trickery

Many of the crews I’ve fished with around the world tend to use similar techniques. These include commonly relying on the teasers set close to the boat to raise the billfish. Marlin have a habit of coming in and checking out the boat’s wash; setting the teasers on the second, third or fourth wave (depending on the size of the vessel) is the answer. From what I’ve witnessed, softhead teasers definitely have the edge, as most times a marlin will keep coming back, either whacking or trying to eat them. At that point, pulling the teaser away from the fish usually further excites a fired-up marlin, which makes the switch easier.

I remember an incident while fishing the prolific marlin grounds off Port Stephens in Australia when we had a 300-pound striped marlin (huge for that species) at the back of the boat ready to switch. In all the excitement, the teasers were pulled out of the water before we could get a bait in. The marlin went crazy looking for something to eat. Even though it became a tease gone wrong, the marlin was so wound up from whacking the softheads, she stayed around, hesitating long enough for us to finally get a bait to her. Strategies for setting up a teaser spread vary from boat to boat, since every skipper and crew have their own preference for the type of lures they run, the colors, and where to place them. The most consistent pattern on many vessels I have fished with is to run two rigged (armed) lures as the longest in the spread for a bit of added action, then placing two or three teasers in a staggered formation closer to the transom.

Since switch-baiting is all about raising and enticing a marlin within range of a boat, getting the teasers working correctly is the first step to raising anything; experimenting with different lures in various areas of the wake is the key to success. The shape and cut of a lure’s head dictate its performance in various sea conditions. A sharply angled face, such as the famous Hawaiian Tube models, work better in calm seas; in sloppy conditions, they tend to jump and bounce about. Even the Mold Craft Bobby Brown Special with its head cut on a hard angle has its limits when it gets rough. The scooped-out (concave) heads, as on the Super Chuggers, or the 90-degree cut of a lure like Mold Craft’s Wide Range, tend to handle most sea conditions far better.

Setting up the pattern of teasers will also vary from vessel to vessel because the hull length and shape make every wake different. The same can be said about the wake from outboard-driven boats compared with inboard shaft-driven boats. Outboard motors emitting exhaust through the propeller create far more bubbles and disturbance than shaft-driven inboards with the exhaust above water. Not only that, there is less sound from inboards penetrating the water, so the general consensus with outboards is to set the teaser spread much farther back.

Placing the teasers on the front of the swell pushed up from a vessel’s hull also helps them track better. The edge of the wash next to clean water seems to be widely preferred as well. Outriggers are important to be able to optimize a teaser spread. Finally, adjusting the speed of the boat to get the combination of teasers all working correctly and not bouncing is the name of the game.

Making the Pitch

Ensuring the success of switch-bait fishing begins with the bait. A boat needs the best possible live baits ready to go. Small fishes in the tuna/-mackerel family such as frigate and chub mackerel and skipjack tuna would rate as ultimate baits no matter where in the world you are billfishing.

Most brands of sabiki rigs come in strings with five or six hooks. When jigging in deep water for large live baits (like chub mackerel), it pays to modify the rig by cutting it down to only three or four hooks at most. Hooking up six large baits at once can end up a disaster, with the rig either so twisted up that it can’t be used again, or the whole string of fish ends up busted off.

Given that you have top baits ready to go, it’s essential that you present them alive and lively. To do that, use standard tuna tubes or smaller custom bait tubes designed for chub mackerel. As Kiwi Capt. Marty Bates once pointed out to me: “It’s a no-brainer using live baits; they’ll get smashed every time, provided the tease is done correctly. The difference between dead and live baits is really chalk and cheese.”

When keeping baits in the tubes for extended periods, a useful trick calls for securing the bridle with a short length of fine copper wire tied to the hook. When the end of the bridle has been inserted through the bait and put back over the point of the hook, the wire is wrapped around both ends of the bridle to keep it intact. It’s embarrassing to pull a live bait out of its tube to present to a marlin only to have it drop onto the deck — or worse, over the side!

Gear Choices

As noted above, switch-baiting allows the angler to choose his tackle to suit the size of the fish raised. Most anglers prefer overhead lever-drag reels for their line capacity, which is essential when chasing blue marlin. Over the past few years, I’ve seen more anglers trying their skills with spinning reels, but the reduced line capacity can be a problem; in that situation, using strong braided line can compensate -somewhat. As a rule though, braid’s lack of stretch creates too many problems with billfish; hooks pull more easily, and line cuts can be a real danger.

Circle hooks are increasingly popular with switch-bait specialists, although some anglers still like to use J hooks when chasing line-class records. With either hook type, it’s important to match the hook to the size of the bait you’re using, particularly considering that baits might range from a half-pound mackerel to a 3-pound tuna.

The length of the bridle is also important. Circles need a bridle much longer than one used with J hooks. That’s because a circle needs to be at least a couple of inches away from (above) the bait so it has enough flexibility to turn once swallowed for a proper hookup. J-hook bridles, on the other hand, need to be kept short so the point of the hook doesn’t turn back into the bait. Circle hooks have an advantage in this department because their shape rarely allows the point to turn back into the bait.

Switch-bait specialists differ on which is the best leader material. A never-ending argument centers on which trace material is best for billfish. Is the good old nylon monofilament trace the best? Or the newer, high-tech fluorocarbon leader? From my experience, monofilament is certainly more popular, and many say it’s still the best. When you get down to the nitty-gritty, two main reasons favor mono. One, fluorocarbon is a lot more expensive. Two, fluoro doesn’t come in the kind of heavy-breaking strains needed for billfish when using medium to heavy tackle. The heaviest fluoro you can buy will test around 350 pounds; on a long fight on the tackle mentioned, it could wear out. For most big-marlin switch-baiters, heavier mono — like 500- to 700-pound Momoi Marlin Ultra-Hard or the tough Ande Premium trace material — is the way to go.

A critical part of switch-baiting is ensuring angler and crew are alert and on deck, watching and waiting. Lying around sleeping or just not paying attention won’t work with this technique. Baits should be rigged and ready; all rigs should be organized and within easy reach. When a marlin is raised, it’s important to slow the boat a little and draw in the teasers. Slowing the boat also gives everyone a better look at the fish because there’s less wash; that also allows the fish to get a better look at the bait when presented.

When the marlin grabs the bait, it’s best to slow the boat to idle or take it out of gear; then, depending on the size of the bait and the style of hook, it’s up to angler or crew to call the shots. Circles need far more time at the strike than do J hooks before the angler increases drag. Striking with J hooks can even be assisted with the boat moving forward again, whereas circles only need the angler to ease up the drag pressure to allow the hook to work its magic and find the corner of the jaw.

About the Author: John Ashley, based in Sydney, Australia, has been running sport-fishing boats along the New South Wales coast for 35 years. He specializes in billfish and yellowfin tuna, traveling the world during the off-season to photograph and write about billfishing.