Fish often bite as the sea stirs. Steep waves and a stiff breeze also whet anticipation for some anglers and enliven action aboard. The downsides are baits and lures that fly more than they swim, drifts approaching trolling speed, and trolling spreads wind-swept into six-line tangles. When the weather downright blows, try advice offered for this article by seven pro skippers on how they continue to entice bites as seas build. “Wahoo definitely bite better when the breeze kicks up,” says Bermuda charter and tournament captain Allen DeSilva. In DeSilva’s waters, that’s 15 knots and 6-foot seas. “Marlin are the opposite. The days we get five, six, seven fish are not rough,” he says.

Adjust Your Trolling Speed

One reason average or calm seas favor marlin fishing is that it’s easier to see trolled lures and fish in the spread. “When it gets rough, bring everything in closer,” DeSilva says, to overcome the decreased visibility.

He also simplifies his overall presentation on bumpy days so that when a bite happens, he can avoid tangles.

For instance, on most days, he runs two dredges and two teasers, followed by lures on his short-rigger and long-rigger positions, plus a center shotgun farther back. “When it gets rough, I’ll eliminate the shotgun and the teaser on one side, but keep that dredge,” DeSilva says. “I’ll [remove] the dredge on the other side and pull that teaser [closer], to where the dredge should be.”

This decreases snarls between the teasers and the short-rigger lures, he says, plus the mates have less to clear when you hook into a fish.

Change Up Lures to Match Conditions

“You want lures deeper when it’s rough, so the fish can see them through the whitecaps,” compared with a normal day, when lure surface action attracts fish’s attention, DeSilva says.

“In Brazil, the seas are almost always hectic,” says Antonio “Tuba” Amaral, a Brazilian charter captain and maker of Amaral Lures. “When the sea surface is confused, lures stay hidden in this turmoil. Lures that dive deeper and longer become more visible to the fish.” Face angle is his key. “My Ta’aora plunger, with a 12-degree face, works better in rough seas than the 20-degree face angle on my Diamondback,” Amaral says.

Amaral places heavier lures on the upwind side when he can, and also closer to the boat so the wind separates his spread. Heavier, ballasted lures also track better when speed fluctuates as boats surf down following seas.

Trolling Baits in Heavy Seas

Whether he’s fishing infamously rough Venezuela or placid Costa Rica, charter captain Bubba Carter runs two dredges with teasers atop, plus swimming ballyhoo on two flat lines clipped to the transom, and two long rigger baits.

“When you’re baitfishing, that’s pretty much the spread, rough or calm,” Carter says. “As it gets rougher, you might want more lead.”

Weight helps hold baits more squarely behind the boat and also keeps them swimming in the water, not skipping on top. Just a quarter-ounce more makes a big difference. He also trolls outrigger baits farther aft. That extra bit of line in the water helps hold the bait down.

Carter occasionally adds chuggers in front of baits to increase resistance on their lines. This also makes baits easier to see from the boat, but he doesn’t believe it’s necessary for the fish. “Just because you can’t see [the bait], doesn’t mean the fish can’t,” Carter says.

Capt. Ronnie Fields typically uses small scoop-faced Mold Craft Chuggers ahead of his baits whether he’s in the Carolinas, Costa Rica or the Caribbean, fishing private or tournament boats. He switches to flat-faced Mold Craft Hookers in rougher water so baits won’t somersault when they pop out of the water on wave crests, which tends to foul circle hooks.

“Pick the bigger baits out of the pack,” Fields says. “They stay in the water better and are more durable. Go up to the next size lead. If we’re using a quarter-ounce, we might go to three-eighths.”

Fields’ biggest changes are in his teasers. “When it’s rough, flat lines blow into the squid chains, so I’ll take the squids off,” he says. “Whatever I would have put behind the squid chain, maybe a mackerel with an Iland Express, I’ll just run without the squids.”

Determining Speed and Direction for Trolling Success

“You can’t troll in the trough for your anglers, but you can’t stay into a head sea for your baits. They’ll be flying through the air,” says Carter. The compromise is taking seas broad on the bow, or quartering the stern, just enough to minimize roll.

Adjust speed in rough water too, although this means two different things: slow engine rpm in following seas and increase rpm in head seas to maintain the same boat speed but also vary boat speed through the water.

Don’t focus on speed over presentation, Fields says. “Look at the baits and make sure they’re not skipping and tumbling.” That might mean increasing engine rpm in head seas yet actually trolling slower. Decreasing boat speed in following seas prevents baits and lures from skipping as boats surf faster down wave faces.

“When it’s rough, you want to turn quickly to get the boat [headed] up-sea or down-sea faster,” Carter says, “but you can’t turn that tight. You’ve got to watch the baits.” His concern is that, with lines already blown off center in the wake, baits on the inside of the turn will slow, which is bad for fishing and leaves baits even more vulnerable to being blown into tangles by the wind.

Be Ready to Adjust Outrigger Halyards

“Watch the baits,” says Fields. “If you see the windy side blowing over too far, adjust that halyard down. Keep the leeward halyards high; that spreads the baits farther apart.” He says it’s particularly helpful to play with halyard height leading into and through each turn.

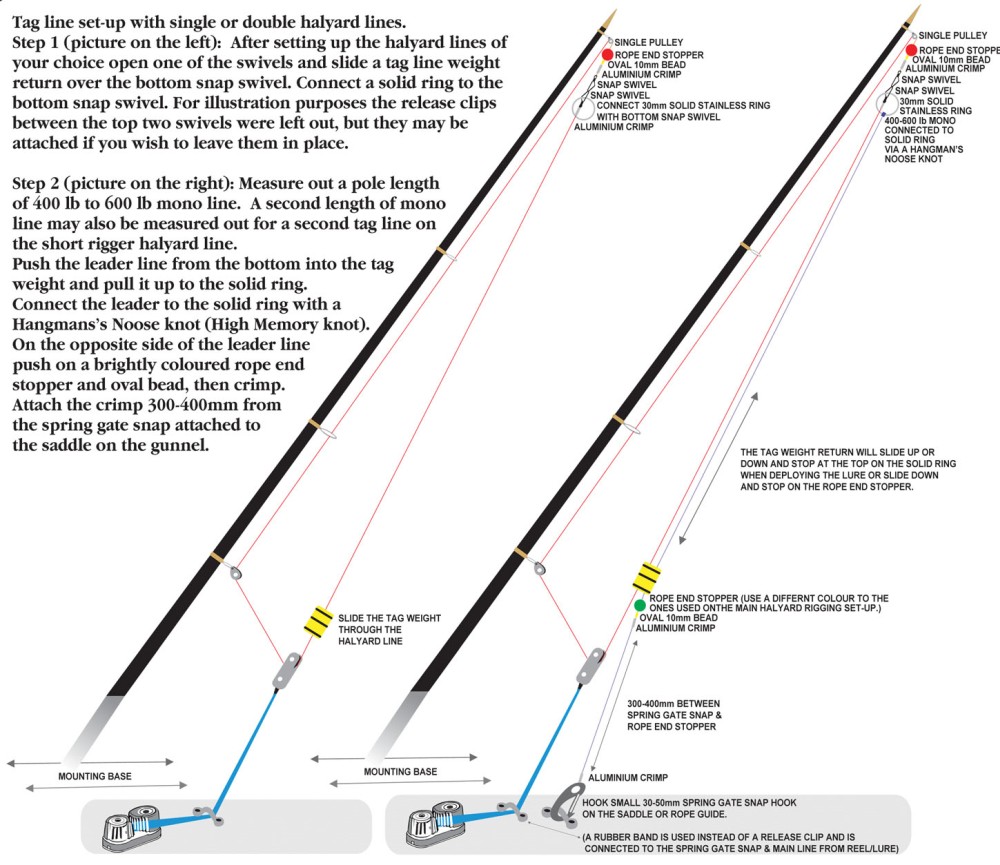

DeSilva runs his outrigger tag lines through halyards to choke them down lower.

Drifting Live Baits in Big Seas

When the drift gets too fast while tuna fishing in the Gulf of Mexico, live baits can’t swim fast enough, so they start to spin, says Capt. Damon McKnight, who owns Super Strike Charters out of Venice, Louisiana. “Free-line it. Just keep feeding line until you get a bite,” McKnight says. “You want zero pressure, with a coil or two of line in the water.”

McKnight also slows the drift by using his motors to hold the boat sideways to the wind. When all else fails, he turns to chunking — throwing over several large pieces of pogy or false albacore with a hook buried deep into one.

“In strong wind, I’ll make the entire drift with an engine or two in reverse,” says Capt. Scott Leonard, who runs Top Gun Sportfishing Charters out of Babylon, New York. “It slows you down to that perfect 2½-knot drift.”

When he’s fishing specific bottom structures for striped bass, Leonard positions his boat with extra leeway. “Start your drift upwind of the structure you’re fishing,” Leonard says. “Watch the GPS and know where you want to be, and maneuver the boat to stay along that line. On your next drift, you’ll know whether you need to start longer or shorter, or this way or that, so your bait is on the bottom as you go past your spot.”

Off Montauk, striped bass often congregate on rips formed where strong current crosses steep ledges. “Seas could be 3 to 4 [feet] off the rip but 6 to 8 right on the rip,” Leonard warns. “If the rip goes from 45 feet to 20 feet, when it’s rough, stay toward the edges of the structure, where it maybe only goes from 45 feet to 30 feet.”

Leonard also uses engines to slow and position the boat as he approaches a rip. “As you get into the rip, be ready to go into forward and drive through it, but let out line at the same time, so as soon as you’re through the rip you can slow the boat and [have the baits] in the right position,” he says.

Kite Fishing in Extreme Conditions

Whether it’s for Miami sailfish or Cape Cod stripers and tuna, Capt. Brett Wilson, who runs Cape Cod’s Hindsight Sport Fishing and winters at the helm for Miss Britt charters in Coconut Grove, often flies kites, even as winds top 30 knots. “Heavy-wind kites are smaller, so they have less drag. That makes them easier to get in and out, but when the wind drops out you have to be ready to switch back to lighter-wind kites,” he warns.

Kite lines change too. Wilson uses 80- or 60-pound braid to reduce weight and drag in moderate wind, but increases to 100-pound monofilament for heavy weather. Monofilament is more resilient than braid, and it won’t cut skin the way thin braid can.

“I prefer to nose-bridle my baits so I can move around, but in heavy wind I’m more inclined to shoulder-bridle [ahead of the dorsal fin] to help keep baits in the water,” Wilson explains. “If a kite hits the water, you don’t want to be in a race to get it. Focus on bait presentation on that other kite.” A small balloon tied where spars cross keeps crashed kites afloat. Back the kite-reel drag way off to keep from folding the kite in the water, and let the wind ease you back to it.

The opposite — no wind — makes kite-fishing particularly tricky. Helium balloons keep kites aloft, but they require either a hint of breeze or slow trolling to draw kites away from the boat.

“Use a smaller, lighter bait and no lead in windless conditions. You’re only fishing two baits per kite, so you might even forgo the cork. Anything to lighten the load and maximize what little wind you have,” Wilson says. “You can even take kite clips off and use a 6-inch piece of telephone wire. Twist it tight to the floss [or swivel], so it doesn’t move around.”

Be Ready for the Bite

Whether seas are smooth or rough, DeSilva connects his outrigger tag lines to Dacron loops on his trolling lines with a loop of 12-pound monofilament. “That means, in rough seas, you know the line didn’t just pop out of a rigger clip,” he says. “That was a fish that snuck up on you.”

Says Fields: “When it’s rough, you can’t see the bite, so you need to feel it.” He directs anglers to hold long-rigger rods, or at least keep a finger on the line, because they can feel that increased tension before the outrigger clip pops.

Fighting Fish in Heavy Seas

“The pointy end of a boat goes into the sea a lot better,” Carter says, referring to his boat’s bow. “Turn bow first, and run up in front of the hooked fish. When you get close, you might have to turn and back into one or two waves to get the leader, but you’re not doing it for 200 yards. Everyone is happier when they’re not soaking wet, and it makes you look good.”

Once hooked up, DeSilva turns immediately down-sea until lines are clear, and then he prefers to chase fish in reverse. Spectra backing on his reels adds line capacity and decreases drag in the water. “Pay attention to the waves as much as the fish,” he warns, gaining line only during smaller sets between larger waves.

In Leonard’s 31-foot center console, he wedges the angler into the corner of the stern, where the boat doesn’t bounce as much compared with the bow, and then runs into the waves at an angle to chase the fish. The bottom line, Wilson says: “Whether the wind is really blowing, or really calm, and whether you’re kite-fishing, drifting or trolling, you have to work hard to keep your presentation correct for when a fish pops up.” Particularly in heavy seas, this comes down to experience.

Don’t make yourself go out when it’s rough just to teach yourself about rough-water fishing, says Carter. “But if it blows up while you’re out, don’t go back home. You’re already there; stay in it and learn.”

Trolling in Calm Conditions

When seas slacken and lie flat, “you want a lure with more action on the surface,” says Bermuda Capt. Allen DeSilva. He prefers a light lure, like those from Fathom, instead of a heavier Black Bart lure he’d troll in normal to rough conditions.

“When it’s calm, marlin are more likely to check out a lure, then move to another, or maybe give one a little tap,” he says.

When marlin won’t eat, DeSilva entices bites by turning the boat left and right so lures cross the wake. “If you get a bite and not a hookup, wind the lure in fast until it pops on the surface,” he says. If that doesn’t work, free-spool so the lure sinks back 20 feet and quickly wind it in again.

When it is really calm, it’s hard to get tuna to bite, says DeSilva. He uses fluorocarbon leaders and nearly double the trolling distance — at least 100 yards aft. Try different lures and trolling lengths too.

“Here in Brazil, tuna are more common during calm seas,” says Tuba Amaral. “I reduce lure size and increase speed.” For flat-sea marlin, increase speed or use a more aggressive lure with a greater face angle to achieve more attractive action.

When it’s particularly calm, tournament and private Capt. Ronnie Fields switches to small spreader-bar teasers instead of squid chains for both billfish and tuna, rigged with three 6-inch squids on each side and six down the middle, plus a chasing mackerel.

“I’ll skip one bait when it’s calm,” Fields adds. “That makes a little ripple, just something to attract attention, and it’s different from the other baits.” Most often he runs the skipping bait fairly close to the boat from the center rigger, to keep it on top, with little or no lead. “We’ll crank it away if a white comes up,” he says. “It makes a good teaser, but we’ll put a hook in it for a blue marlin or wahoo.”

Louisiana Capt. Damon McKnight bump-trolls to keep baits away from the boat, but he often can avoid that practice with bait selection. “Threadfin herring swim away from the boat as fast as they can.”

New York’s Capt. Scott Leonard similarly uses spot or scup, which swim to the bottom with little or no lead, instead of his typical bunker, which tend to stay on the surface.

“Cut a couple of inches off each fork of their tails so they can’t take off like a rocket,” says Leonard.

“When the boat is not moving fast enough, reel in at a steady, slow pace, or try 10 or 15 cranks on the reel, then put it in free-spool. Bam, you’ll get a fish on! On some calm days, that’s half the fish we get.”