Few sharks can compete with the mako as predators; they’re fearless, intelligent, lightning-fast and agile — and one of the world’s greatest game fish. Learn why and how experts target them.

As we worked an edge off Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, where the bottom dropped from 200 to 1,200 feet, a white marlin ate the right short. The fish took off like a bullet, more typical of a blue marlin than a whitey, peeling high-viz off the spool far faster than the boat could chase. The drag-blistering run stopped suddenly, and the boat closed the gap to the weight of the fish still on the line. A few rod pumps brought the marlin up to the transom. The quivering billfish was missing its tail.

There was little speculation aboard about the attacker — only a mako has both the power and speed to sever, in one bite, the beating tail of a billfish running full out.

“It’s a master predator in almost every aspect,” says Dr. Greg Skomal, senior scientist and shark expert at the Massachusetts Department of Marine Fisheries. As one aspect, Skomal points to their coloration. An iridescent-blue dorsal surface masks makos as they swim beneath potential prey. In addition, says Skomal, “that silvery-blue shiny side and white underbelly provide a level of cloaking when they’re attacking from the side. Makos are really well-adapted for speed and stealth in the highly lit upper layers of the open ocean.”

Lamnid Sharks

Shortfin makos, Isurus oxyrinchus to scientists, are one of five species in the family Lamnidae, which includes great whites (Carcharodon carcharias). Lamnids, as they’re collectively called, are the only truly endothermic sharks, generating heat by swimming and retaining that heat through complex vascular nets.

Porbeagles (Lamna nasus), and salmon sharks (L. ditropis), the warmest among lamnids, keep their core around 77 degrees F, even when water temperatures in the far northern and southern seas these sharks inhabit drop into the 30s.

Rare longfin makos (Isurus paucus) are in many ways outliers. Their blunter, dark-colored snout and long, broad pectoral fins — longer than the shark’s head length — suggest longfins are slower, deepwater hunters. They prefer warm seas, particularly near Cuba, off Florida, and around the Bahamas.

(This article refers only to shortfin mako, except when delineating differences with other lamnid sharks. —Ed.)

Built to Be Fast — and Faster

“Makos are open-ocean roamers. Other lamnids can be more coastal,” says Dr. Diego Bernal, biology professor at the University of Massachusetts. “Because of what they feed on, makos have to be really fast” — topping 40 mph when chasing prey.

Endothermy plays a big role. “If your muscles are warm, you can contract them faster,” Bernal explains, particularly of core red muscle for distance swimming. “All lamnids are like high-end sports cars. What’s unique about makos is their white muscle so highly evolved for [speed]. If you look at the biochemistry, a mako’s engine is more finely tuned for short, fast bursts. That’s what makes them stand out.”

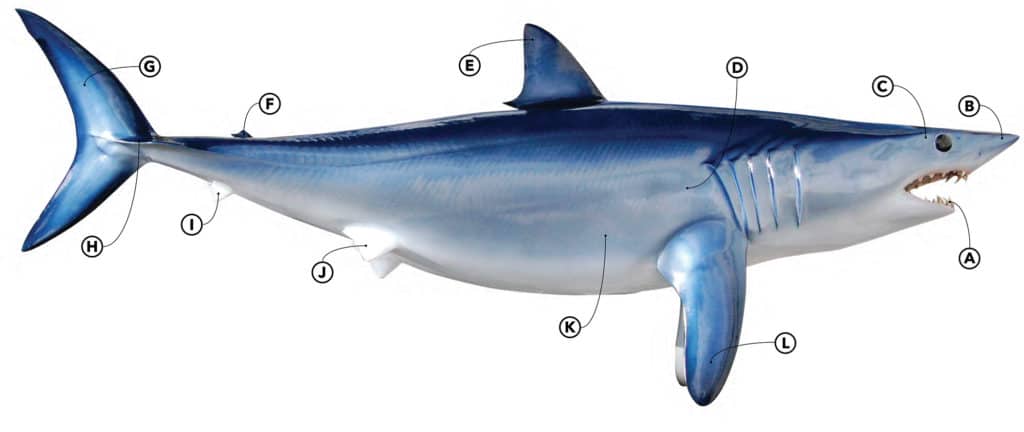

Makos even look fast. “That pointed [nose and its] torpedo shape [are] really well-adapted to moving through the water,” Skomal says. “The small anal and second dorsal fins, shortened pectoral fins, and triangular dorsal fin all reduce drag and increase efficiency.” Caudal keels stiffen the connection from body to tail and provide stability at high speed. Unlike other sharks, the tall, thin, curved tail of the mako and closely related white shark is lunate — having top and bottom lobes of equal size — and closely resembling fast-moving fish such as tunas, facilitating efficient swimming and rapid acceleration.

“Even the morphology of makos’ scales allows as little resistance as possible,” Skomal says. Those scales lie smooth where water flows over them. But wherever a mako’s body flexes such that water would create low-pressure pockets of drag, makos’ scales flex outward and disrupt that low-pressure counterflow.

Such hydrodynamic efficiency actually has little to do with makos’ top-end performance. “They take these really big migrations,” Bernal says. One tagged off New Zealand was recaptured 162 days later near Tahiti, 3,000 miles away, averaging nearly 19 miles traveled per day. Another tagged on the Grand Banks ventured 1,659 nautical miles across the Atlantic in 135 days. Bernal adds, “That nonstop day-in and day-out swimming requires efficiency.”

“These animals know when and where there will be an abundance of food,” says George Burgess, recently retired director of the Florida Museum’s Florida Program for Shark Research. “Sometimes it blows our minds how makos, amazingly, show up in the right place at the right time. When they’re on the move, they get there faster, which gives them a competitive advantage. When you’re first in line at the buffet, you have more to choose from.”

Offshore Observations

Top mako fishermen find those buffets. “The first early-season hard temperature break, when a finger of the Gulf Stream pushes into 500 fathoms, that’s where you’ll see big makos,” says Capt. Stephen Spagnuola, a freelance skipper out of Cape May, New Jersey.

Across the continent, off Long Beach, California, charter Capt. Steven Quinlan reports the same. “You’re looking for the water that warms up first.” For the 800-plus-pound makos he specializes in catching and releasing, Quinlan says: “Their optimal temperature is 67 degrees [off the California coast]. I’ve caught gigantic fish in 71-degree water, but in optimal water conditions, with low chlorophyll count, over structure in areas seals traverse.”

The reverse is true too. “In November, we can have perfect conditions — water temperature, clarity, plenty of bait — and for no reason, the makos will just leave,” Quinlan says. He believes lunar cycles might spur them along toward their next feeding opportunity.

Because they’re warm-bodied, makos acclimate to a wide range of seawater temperatures. When fishing inshore of 100 fathoms near Cape May, Spagnuola says, “in spring, 63- or 64-degree sea-surface temperatures seem best. In fall, they like 55 to 63 degrees at the surface, and we get our bites deeper, at or below the thermocline.”

Shark Heat

Lamnids’ ability to stay warm account for both their temperature tolerance and muscle efficiency (although this seems less-well-developed in longfin makos). Darker, reddish muscle along both sides of the backbone, used during steady distance swimming, generates heat. Structures known as rete mirabile — dense webs of small, closely spaced arteries and veins — perform exactly like a boat engine’s heat exchanger. Heat from venous blood transfers through the rete into cold arterial blood coming from the mako’s heart and gills. By pre-warming that arterial blood, a mako’s core temperature can be 35 degrees above the ambient sea temperature.

This differs from most fishes and sharks, in which gills cool blood to seawater temperature, and that cool blood circulates throughout the body.

Keeping red muscle warm vastly increases its power. Heat also radiates into makos’ white burst-speed muscle, improving acceleration. In yet another advantage, a warm stomach speeds metabolism, allowing makos to turn meals into energy more quickly.

Enhanced Vision

“The mako has a vein that runs right through the middle of the red muscle, from the tail straight to the brain. It bathes the brain in warm blood, and then flows to a heat exchanger that warms the eyes,” Bernal says.

While heated eyes haven’t been studied in lamnid sharks, recent science shows that swordfish key in to changes in light much more quickly because of their heated brain and eyes — not unlike faster refresh-rate televisions that more clearly render fast sports action.

Heightened vision likely benefits makos most during deep dives — some approaching 3,000 feet — where water might be just a few degrees above freezing.

Perpetual Motion

In Bernal’s study of salmon sharks in Alaska, he found that their red muscle works most efficiently when it’s around 78 degrees, but if that muscle cools to just 68 degrees — which is still 30 degrees warmer than their sub-Arctic environment — it would no longer produce meaningful power. Since red muscle is their only source of heat, lamnid sharks have to swim to stay warm, and they have to stay warm to swim.

“The need to swim constantly means makos need more prey to keep up with their fuel demands,” Burgess says. “They’re keyed in to prey items based on energy content.” Makos seek out oil-rich bluefish, mackerel and tuna, and then store that energy as squalene oil in the liver, where it’s readily available fuel for makos to swim fast.

Understanding prey preference is key to catching makos. Quinlan waits to put hooks in the water, pitching baits by sight only to huge makos in his chum slick — he’s boated or released 10 grander makos. “We’ve tried baiting them with yellowtail or dorado. Big makos won’t eat them,” he says. The same holds true with chum. “If you grind up anchovies, squid, maybe some mackerel, you’ll catch small makos. That’s not what the really big ones eat.”

Spagnuola adjusts baits and chum by situation. “In spring [inshore], I’ll use bluefish and mackerel to chum. In fall, it’s bunker and bluefish. In the canyons, I try to get albacore, yellowfin — any pelagic common in that environment.” For baited hooks, Spagnuola uses bluefish or Boston mackerel, but, he says, “false albacore is like candy to a mako.”

San Cocho Swordfish

“Meals are hard to come by in the open ocean,” Burgess says. “Makos have to take advantage of opportunities. It influences who they’ll pick a fight with. Inshore, sharks have a more abundant, predictable menu of easier prey.”

“Makos seem to be fearless,” adds Dr. John Graves, who heads the Department of Fisheries Science at Virginia Institute of Marine Science and is one of Sport Fishing‘s Fish Facts experts. “They’ll take down large swordfish basking on the surface. First they take off the tail, and then the bill, so they have a meal just sitting there.”

Capt. R.J. Boyle has seen more than a dozen hooked swordfish eaten by big shortfin makos, all 500 pounds or larger, in 13 years of daytime swordfishing off Hillsboro, Florida. “They wait it out,” he says. “As soon as a bill or a fin breaks the surface, or the swordfish jumps, that’s when makos attack — always the tail or the bill, never in the middle.”

“When they reach a certain size, makos become specialists at eating billfish,” says Dr. Julian Pepperell, an independent marine biologist in Australia and author of Fishes of the Open Ocean. “Their teeth change. From needlelike prongs for grasping” in smaller makos, which eat small fish whole, “their teeth become more robust, broader and stronger to bite through bone. They bite through the caudal peduncle — the narrow ‘wrist’ of the tail — and completely disable a swordfish or marlin in one bite.”

Studying jaws from fish killed in years past, Quinlan confirms a noticeable change in teeth once makos surpass 500 pounds — when their diets off California favor marine mammals as well as billfish.

In the Atlantic, “I’ve seen two very large makos, both more than 700 pounds, with harbor porpoises in their stomachs,” Skomal says. “One had just a skull, and the other had a whole porpoise around 40 pounds in four pieces.”

Half-Ton High Jumpers

“Makos come up vertically, at incredible speed, and leap out of the water, doing cartwheels,” Pepperell says. “Most likely, they’re coming up underneath prey, but that’s a lot of energy. There must be an easier way. You can almost speculate they’re doing it for fun.”

Quinlan — looking to top a repeat charter client’s biggest fish — once teased an 800-pound mako with a hookless bait. After he denied the bait from the mako repeatedly, Quinlan says, “it went really deep and came up like a rocket and ambushed it.”

“They just run out of water,” Bernal explains. “They hit the surface so fast when going after prey, they fly airborne for 15 or 20 feet.”

Spagnuola sees another explanation. “Makos are the only shark that kill something just because it agitates them,” he says. “I’ve had makos tear up a live bait and never come back to it. I’ve seen them attack other sharks in the chum slick.”

“They seem to understand when they’re hooked that there’s a line connecting them to the boat” Quinlan adds. “They’ll do a jump parallel to the water, [and spin] like a corkscrew, trying to wrap the leader. They’ll try to jump and land on the leader or the line.” Of one 1,000-pound mako, he says: “It went down deep and came up right next to the boat, actually trying to ambush the angler. As it jumped, its tail came right over the gunwale.”

Shark Smarts

“They’re curious; they’re cunning; they’re unpredictable,” Quinlan says. “They’ll try to overtake the boat, get under it, and use the outboards to cut the line. They’ll go straight for marker buoys and kelp patties. They’ll do whatever they can to get away.”

So are makos really smart?

Most of the actions that you might say imply intelligence are stereotypical behaviors that are genetically ingrained, Burgess says. “They’re one of only two shark species I’ve encountered that apparently size up people on a boat” — the other being white sharks, he says. “Makos come alongside, poke their eye out of the water, and stare. It’s really spooky.” Both Quinlan and Spagnuola report similar behavior.

Endurance

In all lamnid sharks, a slippery sheath separates red, distance-swimming muscle from the white, burst-speed muscle, allowing red muscle to contract independently, apart from white muscle, which increases efficiency of cruising mode.

And when speed is called for, Bernal says, “the elevated biochemical capacity of the white muscle allows it to produce more power, and its ability to use oxygen more effectively allows it to recover quickly.”

“If a mako accelerates to catch a bluefish but misses, it’s able to recover from that and be ready to accelerate again quickly,” Skomal says.

“They’re like a lion chasing a gazelle,” Pepperell adds. “The prey tends to tire out sooner than they will.”

Read Next: Shortfin Mako Shark Fishing Mortality Much Higher Than Thought

I expect pro captains to describe their offshore exploits with excitement. But six seasoned, well-respected scientists all expressed awe at makos’ abilities. From all points of view, makos are clearly among nature’s most elite predators.

The science behind the makos’ place at the top of the oceanic food chain is unequivocal. Beyond that science, nothing quite captures the power of these incredible sharks more indelibly for me than seeing that feisty white marlin reeled to the boat san cocho.