Whether trolling, drifting, casting or jigging, anglers’ lures typically mimic live prey. “Sometimes predators know whatever we’re pulling or throwing isn’t the real deal,” says Capt. Damon McKnight (superstrikecharters.com), “but when you put out a real fish with an actual heartbeat, it triggers their brain to attack.” This is particularly true for McKnight, fishing out of Venice, Louisiana, where oil rigs — often far offshore in cobalt-blue water over a thousand feet deep — present for predators permanent smorgasbords of live offerings. For most anglers, live-bait choices can be diverse. How can anglers be sure which to select and how to fish them? Nine professional skippers— spread far and wide — offer their advice here for live-bait choice, as well as tips to produce the most bites.

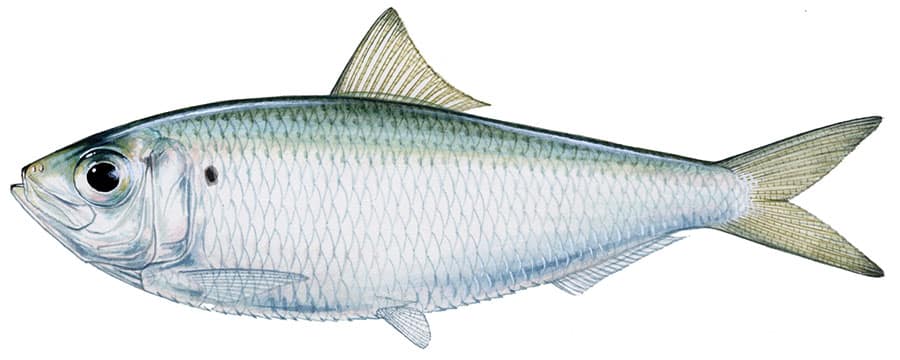

Herrings, Shads and Scaled Sardines

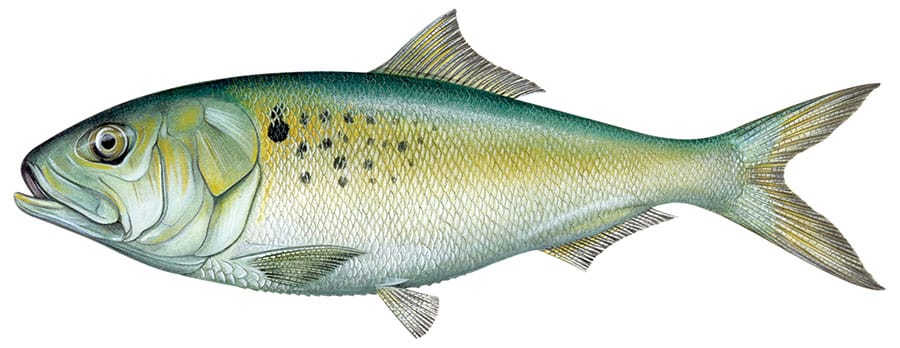

(Bunker)

Brevoortia tyrannus Dawn Witherington

From Cape Cod to Virginia, menhaden are typically called “bunker.” While yellowfin menhaden sometimes get the moniker, it’s generally applied to Atlantic menhaden.

“You can throw a cast net on bunker, but they lose their slime coat and last only a few hours,” says Capt. Scott Leonard, who charters on Long Island’s south shore (topgunsportfishcharters.com). “They actually last longer — a couple of days in a good livewell — when we snag them with a weighted treble hook, as long as their slime coat stays intact.”

“Striped bass eat prey headfirst, while bluefish go for the tail,” says Capt. John Luchka, in Point Pleasant Beach, New Jersey (longrunfishingcharters.com). “Stripers lie beneath frenzying bluefish to get easy pickings. When bluefish bite the tails off live bunker baits, let them sink for a few minutes.”

Luchka hooks 5- to 8-inch bunker just ahead of the dorsal fin, or sideways through the nose if he wants boat mobility.

“Bunker tend to stay on top. If stripers are holding deeper, hook them near the anal fin so they swim down,” Luchka says. Alternatively, he drops live bunker 30 feet or deeper with 2- to 4-ounce egg sinkers, depending on current and desired depth.

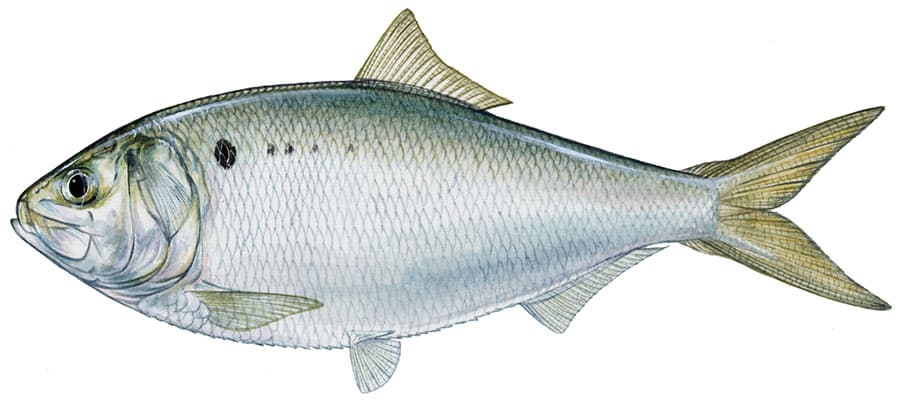

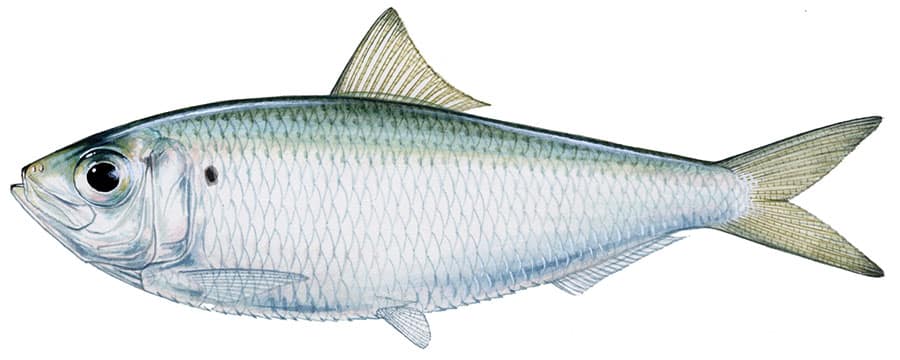

(Pogy)

Brevoortia smithi Gulf Menhaden

(Pogy)

B. patronus Diane Rome Peebles

The name pogy applies primarily to yellowfin menhaden from the Chesapeake Bay through Florida, and Gulf menhaden from Alabama westward and southward.

In Louisiana, McKnight says of the Gulf species, “we catch menhaden in brackish water. They don’t last in the high-salinity water offshore. Recirculate livewell water, instead of transferring in new water, and they’ll last longer.”

McKnight holds the boat up-current of an oil rig and drifts live baits to it. “You have to leave menhaden in free-spool in the current, or they’ll just spin,” he adds. “Hook them either up from the bottom of the jaw or sideways through the nose.”

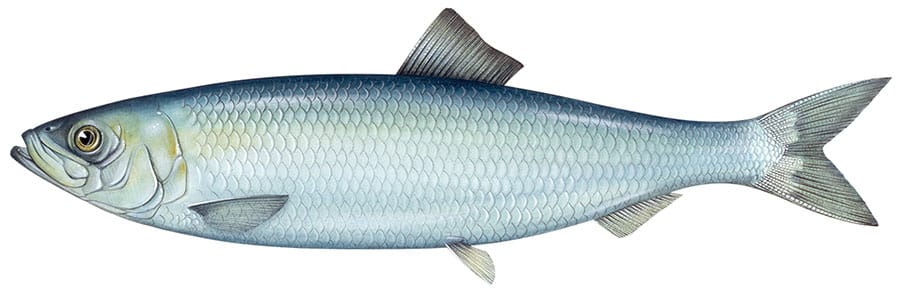

Clupea harengus Dawn Witherington

Some anglers distinguish species, while others lump Atlantic herring, alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), blueback herring (A. aestivalis) and other similar, anadromous (freshwater-spawning) shads together as generic “herring.” Unlike bunker, most herrings bite sabiki rigs.

“We see herring later in the winter or farther north,” Luchka says. “They’re more fragile. Don’t cast-net them like you would bunker.”

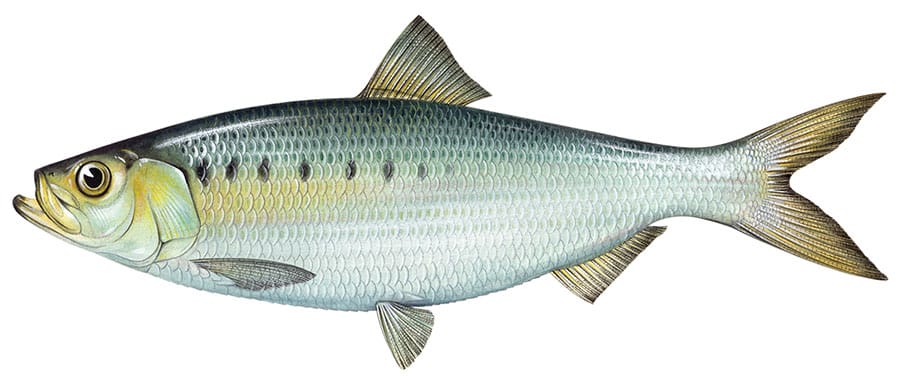

Alosa mediocris Dawn Witherington

In New England, American shad are protected and American herring are tightly regulated because of their importance as bait to the commercial lobster industry. “When you can’t find menhaden, look for hickory shad near jetties where there is good tidal exchange of brackish water,” says Rhode Island-based Capt. Jack Sprengel (eastcoastchartersri.com). “Catch them on sabiki rigs or small bucktails, and fish them just like menhaden.”

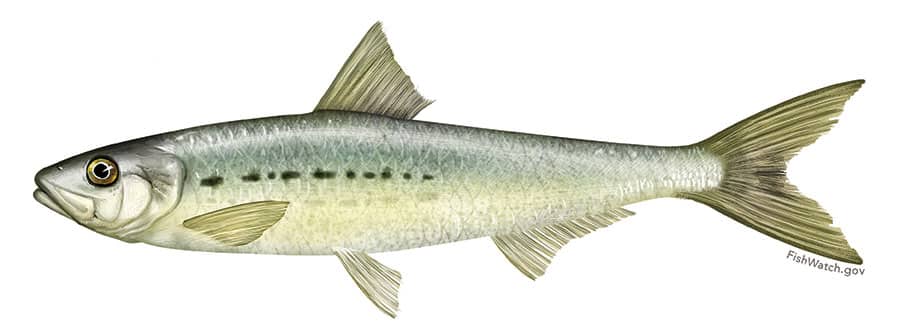

(Threadfin)

Opisthonema oglinum Diane Rome Peebles

Where Northeast bunker are generally heartier than indigenous herrings, the opposite is true farther south. Threadfin are caught in saltier water, so they keep well. “Just don’t put your hands in the livewell,” McKnight warns. “Use a dip net, or [else] sunscreen — or even the oil on your hands — can kill them.”

McKnight hooks threadfin through the back, ahead of the dorsal fin and just behind the bony skull, or through the nose in strong current or to bump-troll. “If I’m using really small hooks, I go right through the eye sockets, trying not to stab anything important,” he adds.

Threadfin are common kite baits in South Florida. “They jump out of the water when they’re chased,” says Capt. George McElveen, from his many years chartering in Islamorada, Florida. “That really triggers the sailfish to bite.”

(Sardine) Harengula clupeola Diane Rome Peebles

“In common use, ‘pilchard’ or ‘sardine’ refers to a group of scaled sardines within the Harengula genus that occur from North Carolina through the Gulf of Mexico,” says George Burgess, director emeritus of University of Florida’s Florida Program for Shark Research (floridamuseum.ufl.edu/sharks).

Savvy fishermen differentiate these baitfish species. “Pilchards are great when fish get finicky,” McElveen says.

In South Florida, he’s referring to Harengula jaguana or H. humeralis. “Throw out a few free baits, and they’ll stay on the surface. Sailfish chase them around and get in a frenzy, and then we sneak a hook into one.” Other baits, particularly any of the scads, immediately swim downward, he warns. “Sailfish chase them, and you never see those fish again.

“We usually catch pilchards with cast nets along the sand-to-grass edges, either inshore or offshore,” he adds.

McElveen bridles pilchards for kite baits just in front of the dorsal fin. When they’re bump-trolled or he wants mobility with kites, that switches to a bridle through the nose. There is one exception, he says: “If you see a sailfish down deep, hook a pilchard in the belly. That makes them swim down.”

(Sardine) Harengula clupeola Diane Rome Peebles

“When sailfish are balling sardines, or eating them on a wreck, sometimes they’ll swim right by everything else just to attack a sardine,” McElveen says.

“They’re our most difficult bait to find and catch.” McElveen says. “Sardines don’t live when caught in cast nets. We catch them with sabikis mostly offshore near the sandy edge along a rocky bottom or reef,” he says.

Southern California’s cool water and strong upwellings bring nutrient-rich waters that sustain large bait populations, and the majority of fishing is done with sardines and other live baits, according to San Diego-based Capt. Barry Brightenburg (alwaysanadventurecharters.com), most often by fly-lining (casting a bait with no weight from a drifting boat).

Engraulis mordax Courtesy NOAA Fisheries

“Dolphinfish, albacore, yellowfin tuna and bluefin tuna offshore, and halibut, yellowtail, bonito and barracuda nearshore all love anchovies,” Brightenburg says. “You can carry a lot of anchovies in a livewell, but they’re really fragile baits.

“Fishing with them is becoming a lost art, but anchovies are often my favorite bait. They require light line and small hooks placed through a small bone at the back of the gill slit or through the nose.”

(California Pilchard)

Sardinops sagax Courtesy NOAA Fisheries

“Compared [with] anchovies, sardines are bigger, heavier baits that are easier to cast farther from the boat,” Brightenburg says. “Sardines are hardier, but they need more oxygen, so give them a little wiggle room. Don’t put as many in a livewell.”

Sardines and anchovies range from British Columbia through Baja. Often the choice between bait species depends on water temperature and

El Niño cycles, Brightenburg says. Anglers often hook sardines through the nose, the back or near the anal fin.

Top Smelt

(Smelt)

Atherinops affinis

“Sometimes catching a few smelt can make your day,” Brightenburg says. “They’ll live in a 5-gallon bucket all day if you add water every 10 minutes,” he says. “Kayak fishermen catch them on sabiki rigs just outside the surf, and slow-troll them along the kelp edge for yellowtail and white seabass, or drop them with a weight for halibut.”

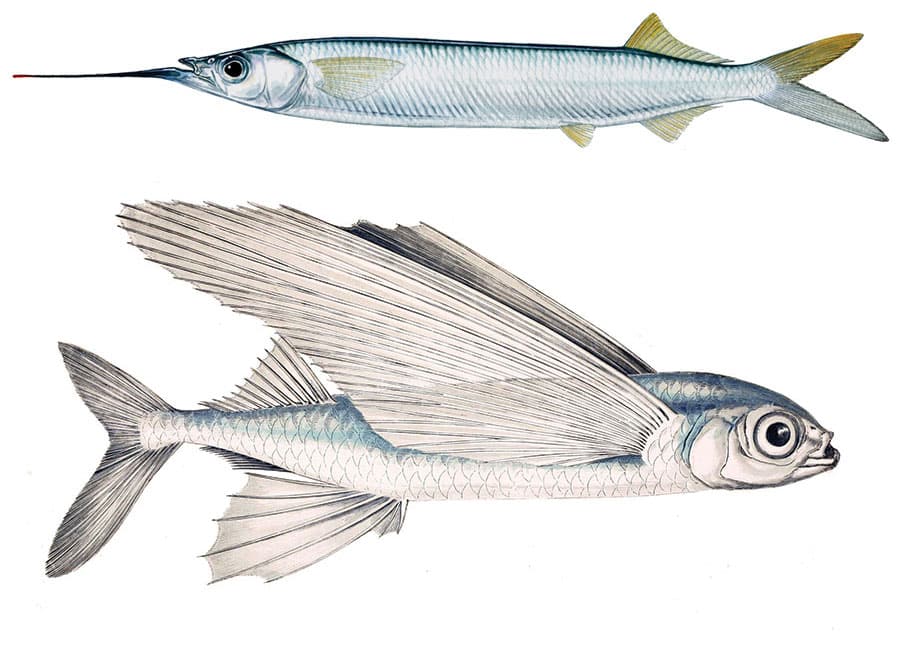

Hemiramphus spp. Flying Fish

Exocoetidae family Diane Rome Peebles, The History Collection / Alamy

These two groups of surface swimmers are closely related to each other within the order Beloniformes. “Their tails have small upper lobes and bigger lower lobes to scoot along atop the surface of the water to escape prey,” Burgess says.

“Bigeye tuna, yellowfin tuna [and] swordfish won’t pass up a flying fish in the canyons,” Sprengel says. “Catch flyers in Hydro Glow lights at night with a dip net, and immediately put them down with 3- to 5-ounce leads. Fish them under a balloon or use a rubber band on the reel handle.”

“Ballyhoo don’t make good kite baits,” McElveen says. “They jump and get tangled in the line, so we put one out on a flat line. When the sailfish first show up in the fall, sometimes they’ll swim right past the kite baits and eat that ballyhoo.

“The hookup ratio is nowhere near as good with ballyhoo,” he warns, so he chooses other baits when he can. “If sailfish are eating ballyhoo, they want something with noticeable scales such as pilchards or herring, not goggle-eyes or cigar minnows with very fine scales.”

Ballyhoo live well when caught in a cast net, though using oatmeal mixed with chum and tiny baited hair hooks will catch the healthiest ballyhoo for use as live bait.

Scads and Jacks

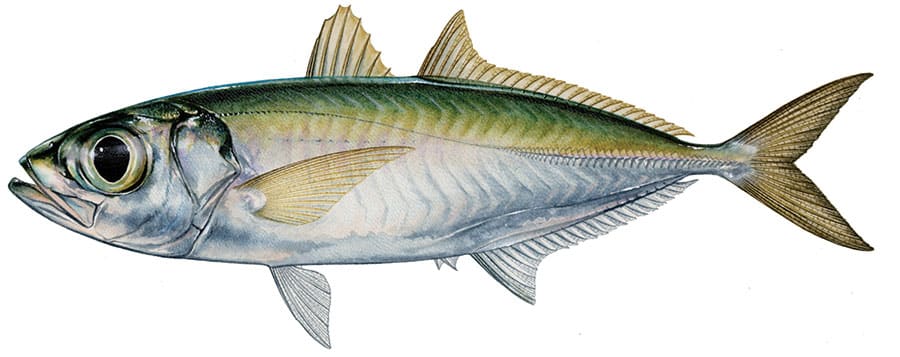

(Goggle-eye)

Selar crumenophthalmus Diane Rome Peebles

Commercial fishermen catch goggle-eyes at night when they school offshore, and then sell them for as much as $100 per dozen or more before some Florida tournaments.

“Sailfish seem to bite them better later in the season,” McElveen says. “They’re a big bait that puts out a lot of commotion over a large area,” which is more easily seen by both fish and anglers, and that extra mass helps keep kite lines tight on rough springtime days.

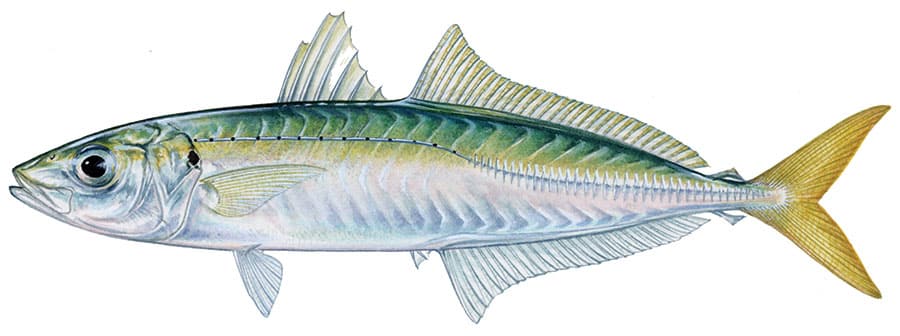

(Cigar Minnow)

Decapterus punctatus Diane Rome Peebles

“Any of the scads roughly the size and shape of a nice Cuban cigar might be ‘cigar minnows,’” Burgess says. In South Florida, cigar minnows typically refer to adult round scad.

“We catch them on the edge of the reef with sabikis, but they don’t bite at night like goggle-eyes,” McElveen says. “They don’t do well from the kite, but while we’re kite-fishing, we might put a couple on the riggers or one on a flat line without weight, and they’ll swim down to cover the lower water column.” Also, he adds, “when the Gulf Stream comes in close to the reef and the water gets powdery, the way cigar minnows swim seems to make sailfish key in on them.”

Redtail Scad (Speedo)

Decapterus tabl

These large, hard-swimming scads shine atop wrecks and prominent structure for big kingfish and wahoo. “Either put out four under a couple of kites, or troll one from each outrigger and one on a flat line. Put another down close to the bottom or wreck. Just tie a loop in the double line, about 40 feet from the bait, and connect an 8-ounce lead with a snap swivel,” McElveen says.

Horse Mackerel

Trachurus trachurus

These scads range throughout the eastern Atlantic. “They’re known here as ‘maasbanker,'” says South African angler and fishing writer Jonathan Booysen (jonofishinglog.blogspot.com). “Slow-troll live maasies hooked through the nose for yellowfin tuna and dorado. Add a wire trace with a stinger hook. For giant trevally, amberjack and bottomfish, I bridle them with a small cable tie and send them to the bottom.”

Yellowtail Scad

(“Yakka” in Australia)

Atule mate

In Australia, these go-to live baits are caught inshore on sabiki rigs, then bridled or hooked ahead of the dorsal or in the nose. “We use yakkas mostly inshore for mackerel tuna and smaller black marlin,” says Australian fishing writer Al McGlashan (almcglashan.com).

Blue Runner

Caranx crysos

“These small jacks get their nickname ‘hardtail’ from their particularly large, rough scutes,” Burgess says. Many anglers see them as alternative baits that prove particularly durable both in the livewell and on the hook, but they’re not really a bait of choice.

Not so, says McKnight: “You might see threadfin far offshore but not on oil-rig structure. We see a lot of hardtails on rigs, though. Sometimes tuna get keyed in to whatever they’re eating at that time on that rig, and you have to stick with that bait.”

There is a downside to blue runners. “You have to bump-troll or they’ll swim right to the boat and get wrapped up in the props,” McKnight says.

California Variants

Blue runner relative green jacks (Caranx caballus) — called caballito along Baja California — are commonly used as live bait, as are tube mackerel (Decapterus macarellus) and a large scad known as chihuil. Long-range tuna boats operating out of San Diego often catch and deploy Pacific jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus), an offshore-dwelling scad.

Tunas and Mackerels

Skipjack Tuna

Blackfin Tuna

Yellowfin Tuna

False Albacore Diane Rome Peebles

While some scads look a lot like mackerel, and even take the name, true mackerel lack scutes, Burgess says. “Mackerel and closely related tuna always have a series of finlets behind the dorsal and anal fins.”

From Cape Cod through Cabo San Lucas, captains live-bait various small tunas, typically bridled through the eyes. Selecting a species — skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), false albacore (aka little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus), Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda), medium-size blackfin tuna (Thunnus atlanticus) and small yellowfin (T. albacares) — often comes down to availability.

“On FADs, it’s hard to pull billfish off that ball of live bait onto a dead bait,” says Florida-based Capt. George Sawley (chittumskiffs.com). “Live bait is very productive, but it blocks the FAD to guys trolling. You have to have boats all working together with live bait, or all working together trolling.”

Sawley often tries live bait on offshore debris. “Use a sabiki and jig up whatever is on that debris,” he says. “I like to put one on top and another down deep on a downrigger with a breakaway.”

Sawley uses small live tuna in the southern Caribbean and Pacific when big yellowfin tuna are on the move. “Fill up your tuna tubes with skipjacks or small yellowfin inshore,” Sawley says, which he does by trolling a small planer ahead of a large sabiki rig with a spoon at the end. (He often makes his own jigs by whipping bucktail material to 1/0 hooks.)

“Drop those live baits in front of the yellowfin, putting one on top and one deep, and you’re going to get a bite.”

Small little tunny, frigate mackerel (Auxis thazard) and bullet mackerel (A. rochei, aka bullet tuna) can be particularly effective live bait. All three look very similar; fortunately, predators don’t seem to discriminate among the three.

(Tinker Mackerel) Diane Rome Peebles

Along Northeast and mid-Atlantic states, tinker mackerel (also known as Boston mackerel or greenbacks) describes immature Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus). In most of the rest of the world, the name refers to fully grown Atlantic chub mackerel (S. colias) and Pacific chub mackerel (S. japonicus). Besides that taxonomical distinction, all three variants of tinker mackerel are nearly identical in appearance and use as live baits.

“We always catch a few tinker mackerel with sabikis or small metal jigs on navigation buoys or offshore on the way out. Then, when we’re offshore running-and-gunning for tuna,” Sprengel says, “if we’re marking fish that won’t respond to topwater plugs or metal jigs, we’ll put one mackerel down with a weight and one away from the boat on a balloon or a kite.”

Live tinker mackerel are also great baits when striped bass are on the move, not sheltered behind structure, Sprengel says.

Off southern Africa, Booysen likes strong-swimming mackerel when trolling faster for yellowfin tuna, dorado or narrow-barred mackerel.

“Along the New South Wales coast, the leading edge of the East Australian Current creates a rich feeding zone,” McGlashan says. Mackerel and scads in thick schools stretch for miles, drawing in predators. “Crews can catch 10 striped or black marlin in a day, and the best way to fish them is with live bait,” McGlashan says. “Mackerel — we call them slimies — are the best bait for everything from marlin to yellowtail. Catch your bait on jigs, bridle them up, and work around the edge of bait schools.

“In addition to billfish offshore, mahi and makos respond well to live mackerel or scads,” McGlashan adds.

Off Southern California, “Pacific mackerel are very hardy if you catch them on a sabiki and use a dehooker to keep their slime coat intact,” Brightenburg says. “We use 8- to 12-inch chub mackerel ‘casters’ when sight-fishing offshore for striped marlin, and we slow-troll larger live mackerel to sunning swordfish. Inshore, live mackerel smaller than 6 inches are great baits for yellowtail, white seabass and halibut.”

Miscellaneous

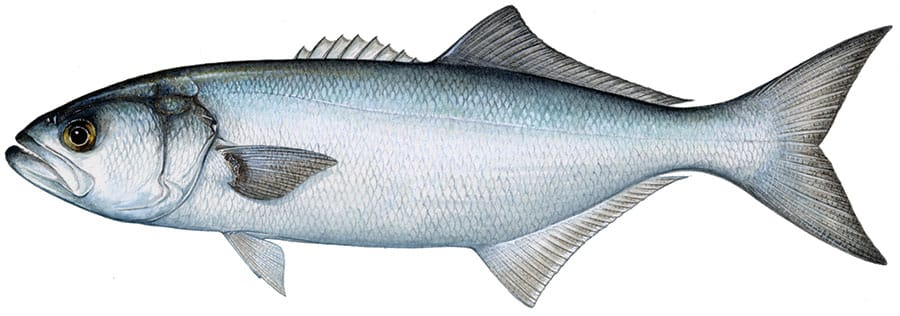

Pomatomus saltatrix Diane Rome Peebles

These relatives to jacks find their way into the spread in temperate waters worldwide. In South Africa, where they’re known as shad, bluefish have a 300-millimeter (12-inch) minimum legal length. “They’re large for a live bait, so they’re easy for predators to see — anything up to 350 millimeters (14 inches) works well,” Booysen says. “They’re not very lively swimmers, but they really wake up with a predator in pursuit.

I use them for levis (a large jack), and we often catch amberjack and giant trevally using live bluefish on the bottom.”

“Giant bluefin tuna seem to really key in on 12- to 24-inch bluefish on a kite,” Sprengel says. “The same holds true for mako and thresher sharks.”

“Bluefish hold well in a livewell, but only one or two for each 30 gallons, depending on the size of the bluefish,” Sprengel adds.

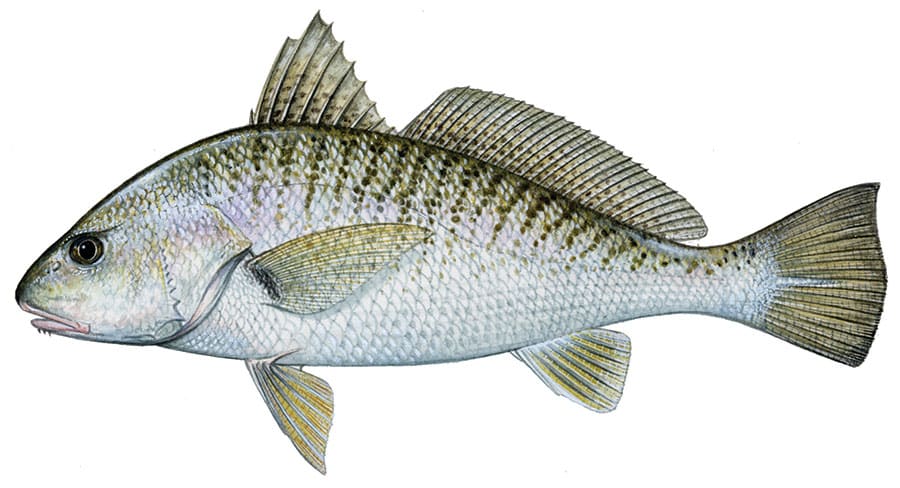

Micropogonias undulatus Diane Rome Peebles

Croakers and spots (Leiostomus xanthurus) are common baits inshore where they’re caught in the soft, muddy bottoms along the U.S. East Coast.

As bycatch from Carolina and Virginia crab traps, they’re also exported as live bait.

“Most of what we used in the past — blackfish, fluke and flounder — now have legal limits too large to use as live bait,” Leonard says. “We catch croakers on the south shore of Long Island once in a while, but most are imported. For striped bass, I drift them near the bottom with a 2- to 3-ounce banana drail (a small, curved trolling lead) and 10 feet of leader with a snelled treble hook through the nose.”

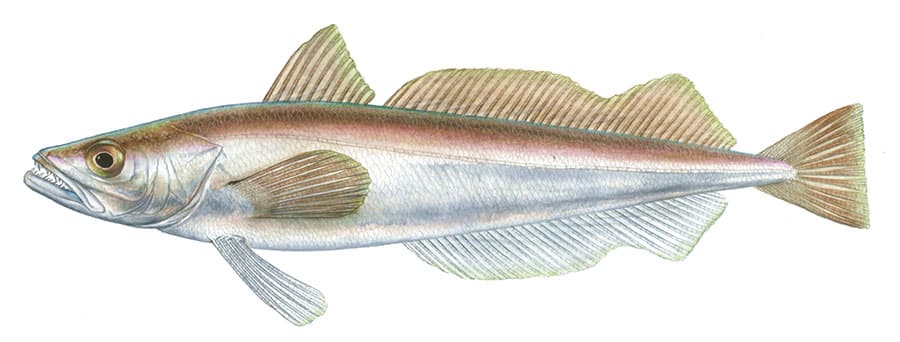

(Whiting)

Merluccius bilinearis Diane Rome Peebles

“They’re harder to catch than some baits, but whiting are a killer bluefin bait. Try a sabiki rig with a little meat on the hooks,” Sprengel says of these Northern bait and food fish. “Hook whiting behind the head, and fish with a breakaway lead off the rod tip or on a balloon at whatever depth you’re marking tuna.”

(Scup)

Stenotomus chrysops Diane Rome Peebles

These hardy members of the Sparidae family are relatives of pinfish. Sprengel bridles them through the eyes and fishes them for striped bass near the bottom in short drifts wherever fast current sweeps over structure. “Some people cut the spines off the dorsal fin, but you really don’t need to,” Spregel says. “Stripers take them head-first right down the hatch, spines and all.”

Mugil spp. Diane Rome Peebles

Live mullet are commonly used inshore but typically not offshore. However, they can be effective at times in any waters.

“Late fall and early winter, mullet move anywhere from 15 to 50 miles offshore to lay eggs,” McKnight says, when they become a preferred bait in the Gulf of Mexico. “For yellowfin, we’ll put live mullet on the surface, where they swim away from the boat, or we might bump-troll them very slowly, hooked through the nose.”

While several nearly identical species inhabit our coastal waters, most common are striped mullet (Mugil cephalus) in fresh or brackish water, and white mullet (M. curema) near the coast, Burgess says.

Anguilla rostrata Diane Rome Peebles

Both American eels and their European cousins spawn in the Sargasso Sea, south of Bermuda, and make their way to the coast from Canada through the Gulf of Mexico, where they eventually live in fresh water until returning offshore to spawn. Bait eels are caught in freshwater rivers, and they’re available regionally in tackle shops.

Sprengel says, “They live for days out of the water. Keep them in a bucket with holes for water to drain out, and cover them with saltwater-soaked seaweed to keep them moist.”

“Stripers smash them,” Sprengel adds. “Use a leader about the length of your rod and just enough weight to hold bottom without hanging up.”

In the mid-Atlantic and northern Gulf, many anglers like to put live eels in front of cobia. “Later in the summer, throw an eel at a buoy or structure and let it swim down deep,” Virginia Beach fisherman Chris Fox says. He hooks them under the jaw and out the eye socket, without lead. When cobia accompany rays, he says, “if you throw a bucktail, you’re likely to foul-hook a ray. Throw a live eel instead, and hold it high in the water, away from the rays.”

“Live baits can be very effective for gamefish, but you can’t just put the bait on a hook and send it out,” Sprengel says. “Deliver it in a way that looks natural to predators. Maybe that means kiting it on the surface, drifting it deep, or casting it to a shallow area with a loud splash. The more you understand how bait and gamefish interact, the better your results will be.”

Squid

Doryteuthis opalescens Courtesy NOAA Fisheries

“Everything eats a live squid,” Brightenburg says. “Squid come out of the deep canyons and return to shallower water in the area where they were born to lay their eggs,” he says of his Southern California waters. “The females die, and that presents an easy meal for white seabass, yellowtail, rays and sharks.

Read Next: Catch More with Live Fish Bait

“They’re easy to cast with heavy line and big hooks,” Brightenburg continues. “Fish don’t have to chase squid, so they expend less energy per calorie.”

Shortfin Squid

Illex illecebrosus

In the canyons, squid snub a jig. “We dip-net them in the lights at night,” Sprengel says of Atlantic squid. “Put them on a 15-foot leader with a circle hook right through the mantle. If there is any current, attach a bank sinker with a rubber band a few feet below the swivel.”

Longfin Squid

Doryteuthis pealeii

“Inshore squid crush a jig,” Sprengel says. “We mark them as big clouds on the bottom machine. They last a week in a livewell with good circulation, but it’s best to put them near the stern and in the center of the boat,” Sprengel says, because motion seems to stress them.