But First! A Little Background: Fishing Poppers and Stickbaits, An Indo-Pacific Phenomenon

Globe-trotting anglers who love to throw lures and sight-fish for a great variety of saltwater game fish associate that fishery mostly with Indo-Pacific reefs. That’s where they can expect to hook up with bad boys of the reefs such as giant trevally, red bass (the aggressive snapper Lutjanus bohar), dogtooth tuna, coral trout, potato grouper, barracuda — you name it.

Using top-shelf spinning gear, anglers fishing these Pacific destinations cast expensive lures in hopes of provoking toothy critters, looking in particular for unforgettable, explosive surface action.

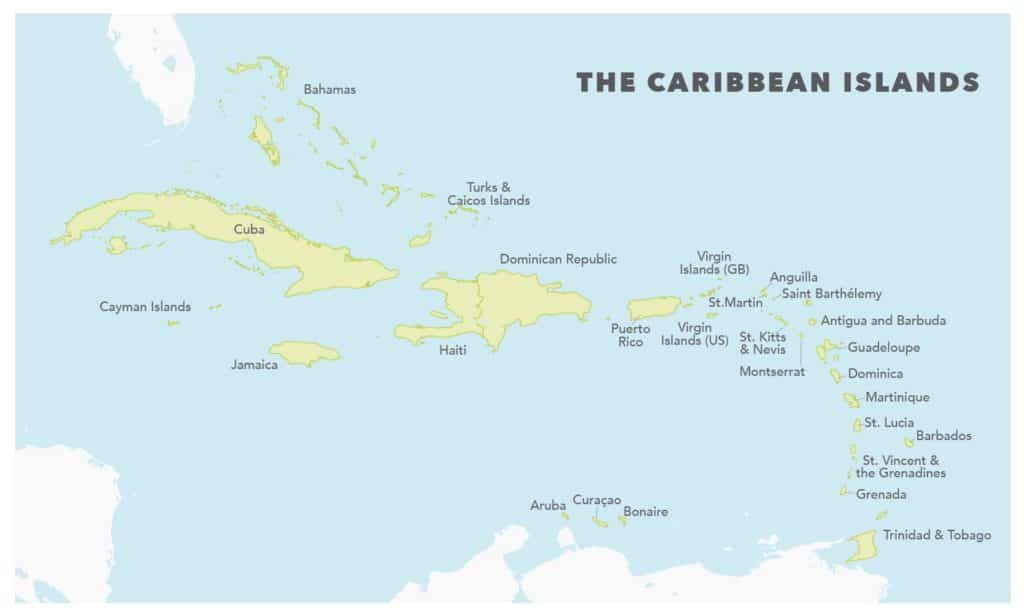

Caribbean Islands: Sight-casters’ Undiscovered Heaven

So yeah, I’ve been there (to many Pacific and Indian Ocean locations) and done that sight-casting thing, but I’ve been elsewhere and done it also — notably around the islands and reefs of the eastern tropical Atlantic. True, the primary draw for many sport fishermen visiting the Caribbean from the United States is fishing blue water and flats. But large areas of deep flats, channels and reefs of rock or coral reefs, found between shore and deeper drop-offs, aren’t fished as much by visiting anglers, especially those who cast and retrieve lures.

This fishery is simply not on the radar of many local guides, who often have no clue about the effective and exciting technique of fishing lures around reefs and shallows. When predators including snappers, groupers, jacks, tarpon, barracuda and others are hunting nearshore waters, all can be suckers for a well-presented lure, throughout the Caribbean — including the Bahamas, Cuba, Trinidad, Mexico’s Yucatan and the cays of Belize and Honduras, as well as many other islands.

“The Lip is Broken Off Your Lure!”

In Caribbean waters, inshore guides often are primarily fly-fishing specialists. They may have little knowledge of lures such as poppers and stickbaits. “The lip is broken off your lure!” is a comment I’ve heard more than once from guides seeing my stickbait who are not familiar with plugs other than diving Rapalas with plastic lips.

I heard just such a comment most recently during a visit to the British Virgin Islands, a lovely paradise at the top of the Leeward Island chain. It was September, the weather was superb, and I had the islands largely to myself. The first morning, my guide stopped his 35-foot center console in a small cove to catch live bait.

I had already tied a 4-inch stickbait to my 30-pound spinning outfit. I threw it out near some pelicans, twitched it twice, and a 30-pound tarpon jumped several times before throwing the lure. A few more casts resulted in another missed tarpon and two nice bar jacks.

We moved on that morning to fish stretches of beautiful coral reef. The water was so clear, it reminded me of atolls of the Indian Ocean. Hard-fighting horse-eye and bar jacks, as well as barracuda, large yellowtail snapper and more species, grabbed my lures. I also lost some unidentified creatures that made off with two of my favorite stickbaits.

In light of the fact that we were just a half-mile from the marina, such hectic action was a nice surprise. The guide admitted he had never caught so many fish so quickly without live baits (which he seemed to forget all about that morning). Thus began three days of exciting fishing around reefs that, surprisingly, probably had never been seriously plugged before.

This experience offered further proof that light-tackle enthusiasts, prepared with the right gear to explore islands in the Antilles and elsewhere in the Caribbean, can find memorable action on hard lures.

The Caribbean’s Jurassic Park for Plug Fishermen

In the early 2000s, Cuba was the first eastern Atlantic destination to which anglers (particularly from Europe) brought serious popping gear with the clear intention of catching big fish like cubera snapper. Huge marine areas around Cuba had been isolated for decades with minimal access or fishing pressure; many Cubans don’t own boats, and there are no modern tackle shops around.

As a result, many fish live long and grow big in these famous protected zones dedicated to divers and fishermen from abroad. Most of the fishing boats available are flat skiffs and can’t easily venture onto deeper reefs, though they offer fishing of world-class dimensions in terms of the variety and size of fish.

A Procession of Game Fish

With small surface and subsurface plugs on the deep flats, channels and shallow reefs (to 20 feet), you can find jacks, ‘cudas, baby tarpon, mutton snapper, young goliath grouper and cubera. These game fish offer great sport on 30-pound tackle.

But if I were casting larger lures over deeper reefs (say, 30 feet or more), I’d think twice before casting with a light rod. Monster cubera and big black and gag grouper patrol those waters. If you don’t have strong, giant trevally-class tackle, and lack much experience battling big fish “street fight-style,” you’ll likely lose your lures and could harm trophy fish.

When fishing big lures along these reef edges, you have no idea what will come up to grab them. It could be a 15-pound jack that ends up being swallowed by a giant cubera seconds after you hook it.

One of those jack attacks happened in the Gardens of the Kings, a chain of keys on the north coast, while we fished a sandy flat, looking for large barracuda. Near Cabo San Antonio, at the western tip of Cuba, we were trying for snapper along a reef drop-off when a school of 15 or 20 AJs showed up and charged all our lures at the same time. Things quickly become chaotic, but at least we were using strong GT rods. Even so, hooking a 50-pound amberjack five feet from the rod tip is something brutal.

Gear That Gives You a Fighting Chance

At best, an angler still makes an awful lot of casts, on average, to hook a prize like a cubera. It’s a shame, then, to lose the fish before getting a good look at it, and if the fish breaks off, you’ve also lost an expensive lure (and, especially if the barbs are still on the hooks, you might have doomed the fish as well).

Guides don’t always have the time or experience to move a boat quickly enough to help the angler keep a big fish away from rocks, caves or coral heads. You need to lock down the drag (at 30 pounds or more) and stop such fish in their tracks. A GT rod with a large, high-end spinning reel, using 100-pound braid, will give you a fighting chance.

When I throw lures around Cuba’s deeper reefs, I generally use 120-pound PowerPro. Lures designed for giant trevally, with the strongest split rings and treble hooks or in-line singles, should hold up. I’ve seen too many anglers relying on 50-pound-test lose nearly every big fish they hook.

Bahamas — Best of Inshore Variety

As most anglers are aware, the Bahamas archipelago is a true paradise for fly-fishermen looking for bonefish. But when it comes to fishing plugs, the potential of these waters is overlooked. Lightweight bucktail jigs, used to target small snapper for dinner, are the only lures I’ve seen in most guides’ boxes, whether at Grand Bahama, Andros or Crooked islands, or the Acklins.

Yet the opportunity the Bahamas offers for light-tackle fishing is immense. Anglers can expect mutton snapper, monster barracuda, smaller tarpon, horse-eye jacks, bar jacks, blacktip and lemon sharks, Nassau grouper, cero or king mackerel, and on and on. I was amazed by the variety of fish I caught while blind-casting lures around shallow reefs (and even in marinas), and I had incredible fun sight-fishing the flats, particularly for big, laid-up barracuda (which are truly explosive in such skinny water).

As one example of the islands’ potential, last February I was invited to spend four days exploring Long Island’s great bonefishing. Sustained north winds, however, had cooled the flats. The bones were hanging off the flats in deeper waters; we caught a few to 8 pounds, but fishing was tough.

Parting Act

On the last morning during my most recent Bahamas trip, before I had to hop on the plane to Nassau, I picked up my spinning rod and box of lures and went for a walk along the rocky beach on the island’s eastern shore, below Stella Maris Resort. Here deep water is close to the rocks. The weather had become superb, the ocean totally and unseasonably flat, and I had this part of Long Island to myself.

I started heaving out a Cordell pencil popper and was rewarded with immediate action from hungry ’cudas. I tried a Williamson Speed Pro Deep, an excellent plug for casting, and immediately caught a beautiful Nassau grouper.

Right after I released the grouper, I spotted a big triggerfish cruising near the surface and tossed a floating stickbait in front of it. I let the lure sit motionless, and the trigger pounced on it, sucking in the rear hook. It was game on.

Afterward, my fourth fish raised was yet another species. Throwing a Williamson popper, I watched a reef shark in triple digits charge — and miss — it, leaving my hands shaking.

The last fish I hooked in the short time I had that morning came in behind that same popper, perhaps 20 yards from shore and in water not much more than 10 feet deep. In a huge swirl of water, it attacked the lure. That wasn’t unlike strikes I’ve experienced fishing GTs in the Seychelles. I saw it well enough to recognize an amberjack of possibly 50 pounds. Had I been in a boat and using heavier gear, I might have had a chance, but this brute charged out on a hundred-yard run before the line passed over a rock, and that was all she wrote.

After that taste, I hope to get back someday and, in a boat with a guide, cast big plugs along the wild side of Long Island.

Caribbean Snappers

Once hooked, muttons rush to find shelter in a cave, under a rock or a coral head, or even in a hole in the sand. Using 30-pound braid is a minimum if you are targeting muttons of 10 pounds or more. Unlike their cousin the cubera, which prefers a slow retrieve and frequent pauses, muttons are prone to going after sinking stickbaits worked with dynamic twitches (pauses too long give these sharp-eyed fish time to rethink the wounded baitfish). They also respond well to lipped diving minnows the size of big sardines, and where muttons remain abundant, they will take surface lures.

Pick Your Plugs

Stick baits cast long distances and swim with an underwater walk-the-dog motion, typically just a bit below the surface. For lighter duty, 4- to 5-inch sinking Sebile Stick Shadds, Shimano Orcas and the like will turn on everything from yellowtail snapper to big tarpon. Floating stickbaits might be less effective overall but are more fun. Besides the classic red-and-white Zara Super Spook, there are many other options, including floating models of the Stick Shadd and Orca, as well as the Rapala X-Rap Walk.

Work big lures slowly. That’s one key for success with cubera and big grouper: Using sinking stickbaits, employ a slow retrieve with many pauses lasting a couple of seconds. Similarly, with big poppers, retrieve with strong jerks and a stop every 10 yards or so. Be on guard, because vicious attacks often happen when the lure sits motionless.

Leader Lore

Forget wire leaders; 2½ feet of fluorocarbon or hard mono is better. You might lose a few lures to the teeth of barracuda or king mackerel if you’re unlucky, but you’ll have plenty of bites, and it will be easier to control fish boat-side. Connect braid to leader with an FG knot. When fishing 30-pound line, I use 50-pound fluoro and check it after every fish or strike. With heavy tackle, using 100-pound braid, for cuberas, don’t go under 150- or even 200-pound-test for leader.

Crimped sleeves offer an alternative to tying a loop knot with very heavy mono leaders, though not a lot of anglers use them. (But in any case, I like to carry a big Hi-Seas crimping plier because it will cut through a large hook and adds a measure of safety when fishing remote areas.)

Hooks

With most smaller plugs out of the package, the standard treble hooks will last about two seconds if you hook even a 10-pound snapper on 30-pound line. Plan to replace the hooks (and split rings) from the get-go with strong hardware, as this Caribbean-reef plugger has done.

For heavy poppers and sinking stickbaits, you should have 250-pound split rings and serious trebles, or the biggest single jig hooks rigged with a short 300-pound assist cord. (Don’t forget to carry pliers designed to open heavy split rings.)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR