I suspect that the fly-fishing gene had always lay dormant in my angling DNA. Inklings of it surfaced early in life when, at age 26, I signed up for a summer freshwater fly-fishing class at the local recreation center. But it was never to be. A day later our 18-month-old first son contracted life-threatening spinal meningitis, and all other plans faded to pale memories as my wife and I spent weeks at the hospital overseeing his treatment and, fortunately, his recovery. My wife was pregnant with our second son at the time, and little did I know that he would become the person to introduce me to fly fishing. It just took 44 years to get there.

In the autumn of 2023, I traveled to northern Utah where my middle son, Joshua, now resides with his wife and two kids. The plans had called for fishing a big lake called Strawberry Reservoir to troll for kokanee salmon — a strain of landlocked sockeye salmon known for its great taste. But gale winds had different plans, putting a halt to venturing out on this high-mountain lake and risking treacherous weather.

A Fly-Fishing Plan Comes Together

Joshua instead organized a float trip with his buddy Jeff Harwin on the lower Provo River to target big brown trout. Harwin runs Park City Flyfishing and Joshua is one of his guides, but this trip would be busman’s holiday for both of them with a caveat: fly fishing only. More to the point, dry flies exclusively.

“Woof!” I exclaimed. “You guys know that I have never fly-fished. Like ever.”

“That’s Okay!” Harwin hollered to me in the front of the boat, above the din of roaring Provo waters as we pushed into the first set of rapids. “It’s easy,” he said, while working the oars. “You know how to fish, so you’ll learn quickly.”

I turned to Joshua with a WTF expression. He was less reassuring. “The river’s moving pretty fast and we have gusty headwinds, so you’re going to have to cast quickly and with some power to hit the prime spots. Just listen to Jeff and do exactly what he says.”

Trouble with the Backcast

As we entered a slow section of the river, Harwin began calling out spots. “See that undercut bank on the left just ahead? Put your fly tight to the shore!” he barked. But rather than focusing on the spots, I grew concerned with my backcast, a cautionary precept drilled into the minds of West Coast saltwater anglers from a young age to avoid injuring anyone behind you. I missed spot after spot, and was beginning to think I would never learn.

“Don’t worry about the backcast,” Harwin said. “If you’re casting correctly, you won’t hit us. Stop that side-arm $#*!. Hold the rod high on the back cast, wait for it to load, and then come forward. The line will go well over our heads.”

I drew a deep breath and tried to relax while keeping Harwin’s coaching in mind. Joshua, an expert fly-caster in his own right, remained remarkably silent, knowing that Harwin possessed decades more experience and sensed that I might reach a point of overload if he too piped in.

My First Brown Trout

My fortunes turned around as we exited the next section of whitewater and slipped into the roiling pool below. “Put your fly next to the fallen tree,” Harwin said. I amazed myself by hitting the target. “Now give it a big mend up river.” I complied. “Good job, now let ’er hunt.”

Seconds later, a nice brown trout rolled on the dry fly, and I set the hook. This is what I came for. Harwin coached me through the fight. His first command: “Get it on the reel!” I let the excess fly line slip through my fingers. “Hold that rod high and keep a big bend in it, and keep your hands off the reel until I tell you to reel,” he said.

The last thing I wanted was to break off the first fish I ever hooked on a fly. That would piss everyone off, including me. So I followed Harwin’s advice to a tee, except for one little mistake. I kept lowering the rod, a habit born of years of battling saltwater fish in which high-sticking is a cardinal sin. “This isn’t saltwater fishing,” Harwin barked. “Get that rod high! Once it stops bending, crank in some line.”

After what seemed like an excruciating amount of time, the brown trout finally slipped into the landing net. Joshua finally spoke up. “That’s how you do it Dad,” he said, his voice cracking. For all of his outdoorsy toughness, like his mom, he is an easy cry. Not only was this my first fly-caught fish, but also my personal best brown trout, estimated at around 18 inches before we released it.

A Lean, Mean Fly-Fishing Machine

We went on that day to land six more brown trout amid nearly twice as many “eats” on dry flies between Joshua and I before reaching the haul-out point. Both Joshua and Harwin later admitted over lunch that my introduction to fly-fishing—indeed dry-fly fishing, the pinnacle of the sport—took place under some of the worst conditions possible. They were pleasantly surprised that such an old tyro could prevail.

The next day the weather improved, lending us an opportunity to visit Strawberry to troll for kokanee. “That’d be nice, but I’d like to go fly-fishing again,” I said to Joshua. His eyes lit up. “I know right where to go.”

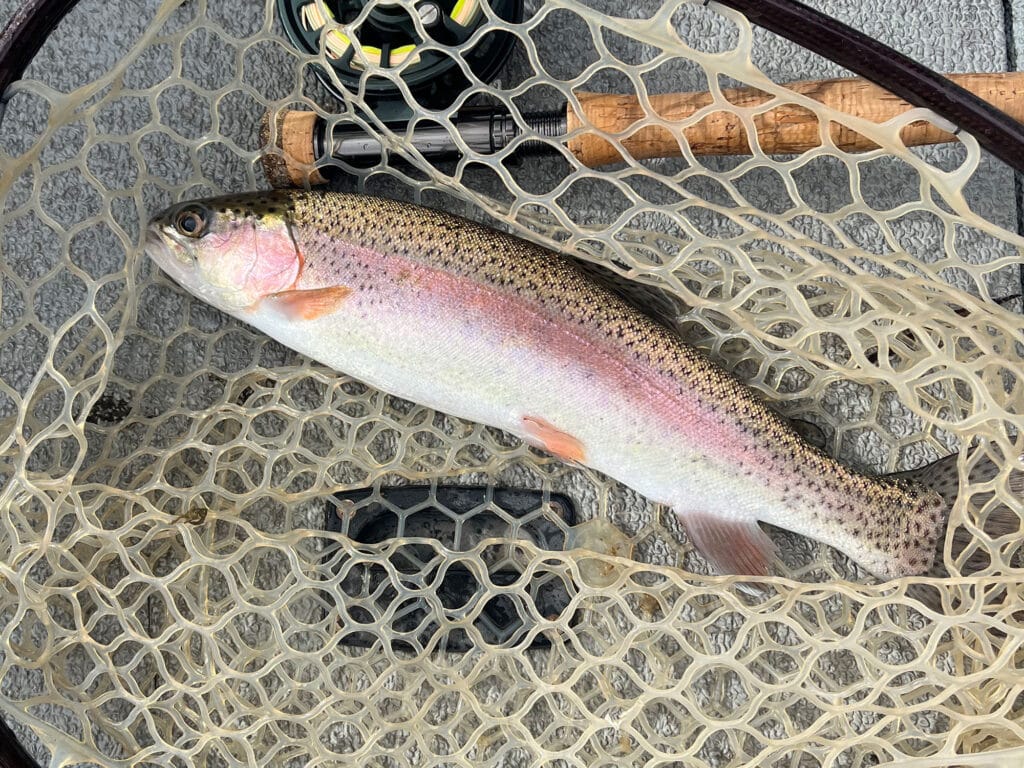

We hooked up the Lund aluminum fishing boat and headed out to a beautiful lake in a picturesque high-mountain valley in the Wasatch National Forest, and for four solid hours caught rainbow trout, cutthroat trout and Arctic grayling (a bucket-list species for me). We caught and released more than 50 fish, giving me an incredible opportunity to hone my fly-fishing skills. I fished nothing but dry flies, even when Joshua asked if I wanted to try fishing a nymph. “Nope,” I answered. “I’m hardcore now—it’s dry-fly or die.”

Yes, I definitely possess the fly-fishing gene. As such, there’s a lot catching up to do, and I plan to enjoy every minute.