I was worried that something was wrong: My normally exuberant 14-year-old son had withdrawn into our dark, dusty shed, and remained hidden away all afternoon. This is a kid who usually walked down to the jetty to cast topwaters at daybreak, played basketball the rest of the morning, spent the afternoon with a lacrosse stick in his hands, and then hiked back down to the jetty rocks for the sunset bite.

When he finally burst into the house, the reason for his divergent behavior became clear.

“Look what I made, Dad!” he shouted, holding up a 6-inch chunk of malformed wood painted red on one end and white on the other. It had divots where he’d whittled too deep, bulges where he hadn’t shaved enough, burrs where he’d failed to sand, and a pair of treble hooks as big as grappling anchors swinging from its belly. It was both the ugliest and the most beautiful topwater plug I’d ever seen.

When the sun approached the tree line that evening, Max sauntered down to the jetty armed with his custom-made weaponry. About the time I started glancing out the window, beginning to grow worried, my cellphone rang.

“Dad, I need to you to come pick me up,” he panted into the phone. “And bring a cooler. The big cooler.”

The striped bass we ate that night tasted good to me, but to Max it was surely the sweetest fish ever cooked. That gorgeous pig of a plug was immediately retired to a place of honor on Max’s windowsill, and the next day he began work on another.

A sense of self-satisfaction goes with enjoying something you’ve created. Experiencing this feeling can have a lifelong impact. When you speak with those lucky few who have built careers on building lures, you discover that this sense of satisfaction is only one of the rewards to be reaped — you also get to saunter down to the jetties, beaches and docks a bit more regularly than those with more-traditional jobs.

The Pioneer: Mark Nichols

Most anglers should be familiar with the name D.O.A. Lures, though they might be a bit less familiar with the man behind the brand: Mark Nichols. Nichols got his start making lures at an unusually early age, when he snagged his sister’s Creepy Crawlers kit (a toy consisting of low-melting-point plastic, a lightbulb-powered mini oven, and bug molds) and began making his own plastic worms as a kid in Houston.

“Dad owned a shrimp boat, and I was raised fishing,” he says. “I was always fascinated by what would get a fish to eat. Even just tossing crickets into a pond and watching bluegill snap them up would hold my attention.”

This natural fascination, combined with Nichols’ exposure to molding, would evolve into a business. In 1981, he started D.O.A. near Stuart, on Florida’s southeast coast. He chose the name “D.O.A.” simply because he figured people would remember it.

“I carved a shrimp and became obsessed with getting it to do what I wanted it to do in the water,” he explains. “I would see a snook lying in the current, just like a trout lies in the current in a stream, then start hacking on the shrimp trying to make it move like the real thing. I wanted to be able to finesse that snook into eating.”

Nichols learned how to cast molds, initially making them out of epoxy, and then went to a mold builder to have them formed in aluminum. “They said I couldn’t make the shrimp with legs and eyeballs because it was too complex,” he says, before laughing and then adding, “fortunately I don’t always follow all the rules.”

To find inspiration for his next creation, Nichols simply goes fishing. “Sometimes it happens overnight, and other times it takes years,” he says. “Others come to fruition quickly but are followed with an evolution.”

That original shrimp, for example, started with a treble hook, then was rigged through the body with a double hook, and eventually became the single‑hook lure it is today.

Another example of pioneer-style rule breaking came when he tried to create a lure that mimicked pinfish. “It’s called the Tough Guy,” Nichols says. “Usually I carve from wood, but not that time. To get it just right, I took a live pinfish, froze it, and cast the mold from the actual fish. Today we ship about 10,000 of them to the Christmas Islands alone. Their profile is so similar to the butterfish there that they’re very effective, and the fishermen there love them.”

The Determined: Ben Patrick

The Halco Tackle Company, located in Fremantle, Australia, dates back to 1950. The company initially focused on metal lures and remained relatively small, but in 1980, Neil Patrick, an IGFA Hall of Famer and Trustee acknowledged for his “lifetime contribution to the sustainable future of the recreational fishery on a global scale,” bought Halco and expanded the business to include a wider range of lures.

In 2001 he handed over the reins to his son Ben Patrick, who has grown Halco into the largest fishing-lure manufacturer in Australia. Ben grew up fishing with his father, chasing everything from herring to blue marlin.

All the while, the young lure-maker kept his focus on improvements he could make to current products, and lures he wanted to use that simply didn’t exist. In speaking with him now, one of the reasons for his success begins to emerge: dogged determination.

Despite all the tech available to manufacturers today, Patrick still begins the lure-making process with old-fashioned on-the-water experimentation. “That’s where I identify the need,” he says, “and the opportunity.” When he wanted a large, stable lure to cover a lot of ground, he started working on the Max 190, which can be trolled up to 20 knots.

Midnight brainstorms and deep thought comprise the next stage of the process, which gets Patrick started on a basic design. Often in the early stages, he uses pieces and parts from Halco’s existing lures to Frankenstein something together. And he notes that although a lack of success might feel like a setback at first, it can be just as important as anything else since it helps him put the lure-design puzzle together, and define parameters.

With the initial fieldwork under his belt, Patrick begins utilizing the technology that so many manufacturers of all types now depend on. “Digitalization has made a vast difference,” he says. “I used to cut things out of wood and plastic, then once completed, reverse-engineer it for the die-making process. But today, multiaxis CNC machines and 3D printing have made prototyping faster and allow us to be testing a product without the need to reverse‑engineer it at the final stage.”

Then, it’s back to the water: first in a small tank they keep in the factory for testing lure designs, then on to the pier in front of Halco’s office, and from there out into the wider world. Testing takes place not just in Australian waters, but essentially across the globe. Preproduction lures have been sent overseas to be tested in waters as varied as those of Malaysia, Egypt and even the Canary Islands.

“One thing I’ve learned, and often through bad experiences, is that the forces of tough fish and Mother Nature can throw a curveball at your design,” Patrick says. “It’s then time to head back to the ‘lure room,’ nut-out the problem, and find a solution.”

That determination can lead to great rewards, and we’re not just talking about the financial ones. A good example is the Roosta poppers, one of the designs for which Patrick is most proud. “After fishing with various poppers for a long time, I decided that we could put some technology into a very simple design to get a far superior product,” he says. “That got me on the path to finding the key design features that would improve traditional poppers.”

The Roostas resolve popper problems such as erratic operation in rough conditions. They’re rattle-equipped, injection-molded poppers with a large, concave head that transitions to a widened tail end. They make a big bloop and lots of rattling noise, and minimize cartwheeling. “What I enjoyed was overcoming the perception that a popper is a very simple bait,” Patrick explains, “and developing a product that was different from the others and overcame the inherent problems with them.”

The Dreamer: Patrick Sebile

Patrick Sebile has been designing lures since he was just 8 years old in his native France. At the time, French anglers could find a few Rapalas, Mepps and tin jigging spoons, but that was about it, Sebile says. The love of lure-making was first born out of necessity but evolved into what might accurately be termed an obsession.

“JFK said we go to the moon because ‘we choose’ to go to the moon,’” he notes, paraphrasing the former U.S. president’s 1962 speech. “And so I say, we fish with lures because we choose to fish with lures. Now and forever — not because it is easy, but because it is hard; because this way of fishing is what makes us anglers instead of fishermen; because this challenge is one we are willing to accept and unwilling to postpone — and one we intend to win.”

We should note at this juncture that Sebile became a proud American citizen just over a year ago and lives on the central Florida coast, so he currently might be a bit more enlivened by our country’s history than the average Joe. Be that as it may, as someone who has stayed on the cutting edge and utilized technology to its fullest, he’s also someone who’s earned his place in history — the history of lure-making.

“I remember carving my lures for many years, and then having them scanned to create a 3D file,” Sebile explains. “But 20 years ago, I was introduced to stereolithography, a process that allowed me to get a 3D print of a prototype. Two ‘eyes’ shoot lasers 90 degrees from each other into a tank filled with a kind of gelcoat. Where the two rays crossed created heat, which turned the liquid into a hard dot. Spot after spot, the 3D drawing was turned into an actual reality. Then we could test the prototype for balance and swim, and make more prototypes until the lure was almost perfect. We could produce the production mold with confidence. Today’s 3D printers are a much faster evolution of this, but an evolution only. That was truly revolutionary.”

No longer working with the company that bears his name nor its parent Pure Fishing, which bought the line a few years ago, Sebile has launched a new series of saltwater lures called Ocean Born, debuting at the tackle industry’s trade show this year.

While tech might make the process faster, it doesn’t always make it easier. When asked which of his lures he’s most proud of (“You’re asking a lure daddy to choose between his baby lures?!” he protests), Sebile points to the Onduspoon.

“It was the craziest and toughest development of all my creations — ever — with a development spanning two years and close to 100 prototypes,” he says. “I almost gave up twice, thinking it might not be possible to achieve my goal: developing a spoon that was able to swim without twisting the line.”

Develop it, he did. On, to the moon!

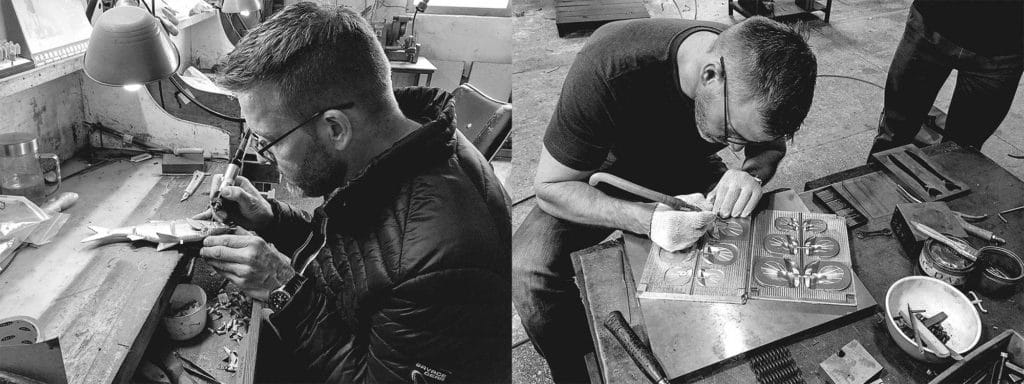

The Mad Scientist: Mads Grosell

Although you may never have heard the name Mads Grosell, nor that of the Copenhagen, Denmark-based company Svendsen Sport, you’ve almost certainly heard of the lures Grosell develops, which we use here in America via the Savage Gear brand — including last year’s headline-grabbing 3D Suicide Duck.

That unusual, though mostly freshwater, lure not only won an award for Best New Hardbait Lure at the 2016 ICAST fishing-tackle trade show, it also turns out to be one of the creations for which Grosell is most proud. Some might say that using a lure like this is “fowl play,” but to Grosell, those little duckies represent obvious prey.

“The lure-making process begins when I’m in a fishing situation and I’m missing a tool in the box,” he explains. “Or I have a crazy idea that’s so out there, I know it will work.”

But as is the case for many lure-makers, this doesn’t mean a departure from reality so much as a clearer look at it from new angles. “We’ve gone through a lure-making revolution,” he says. “For me, 3D scanning of real prey, the development of oversize lures and terrestrial lures, and the quality and realism of lures have all contributed.”

To Grosell, this revolution doesn’t just mean catching more fish, it also means enticing newcomers into fishing, which is one of his personal missions. “I want to change the industry for the better, and make it cooler,” he says, “reach younger people, and get more newcomers.”

Considering that he began fishing as a young child, catching shiners with his brother Martin and trading them for fishing trips, perhaps his fascination with what might be termed “startling realism” in lures shouldn’t be too big of a surprise. Nor should his final bit of advice to anyone who might dream of one day of becoming a lure-maker: Think outside the box, and innovate.

The Kid at Heart: Michael Hogan

Hogy Lures is a relatively new company, having started more or less by accident in 2004 when Capt. Michael Hogan began making large, soft-plastic baits for use on his own charter boat running out of Cape Cod. After giving a few to friends who immediately began referring to them as “Hogys,” Hogan began hand-pouring the soft plastics to sell. But even then, he was no stranger to molding baits.

“Making my own lures was my mom’s fault,” says Hogan, who grew up in 1980s Boston. “When I was 10 or 11 years old, she bought me a make-your-own-rubber-worm kit. It came with a ready-made mold, some liquid plastisol, coloring and instructions on how to make your own molds out of plaster. Stinky as it was, it was pretty easy to do and still is. I still remember the first fish I caught on my own creation.”

Hogan’s overall love for lures, however, dates back even further — to his first fishing memories: “My dad came home one day with a dingy and a set of oars hanging out the back of our giant Malibu wagon, ready to take my sister and me fishing,” Hogan recalls. “I must have been about 4 years old, my sister would have been 8, and the details are a little foggy. But I very clearly remember sitting in the back of the boat engulfed by a giant orange life vest, while holding a push-button Zebco rigged with an Al’s Goldfish wobbling lure behind us. I will never forget the thrill I had when the rod started bouncing. I’ve loved lures ever since.”

Today Hogan’s line — based out of Falmouth, Massachusetts — covers the gamut from soft plastics to jigging spoons to squid bars. Although he still holds his captain’s license, he says he doesn’t run trips anymore. Now he spends the bulk of his on-water time using Hogys while filming how-to videos for the company website as well as his personal blog, saltycape.com.

Read Next: Topwater Fishing: A Guide to the Most Popular Lures

Hogan recaptures fishing memories with his own children — ages 5 and 7 — when he takes them for scup and sea bass just outside the harbor. “The wonder of the surroundings of nature, the bonding, the escape from worries that stay on land,” he says. “I’m reminded what fishing is all about every time I take my son and daughter and see their eyes light up [when we catch] a fish, and the high-fives that follow.”

Wood Craftsman

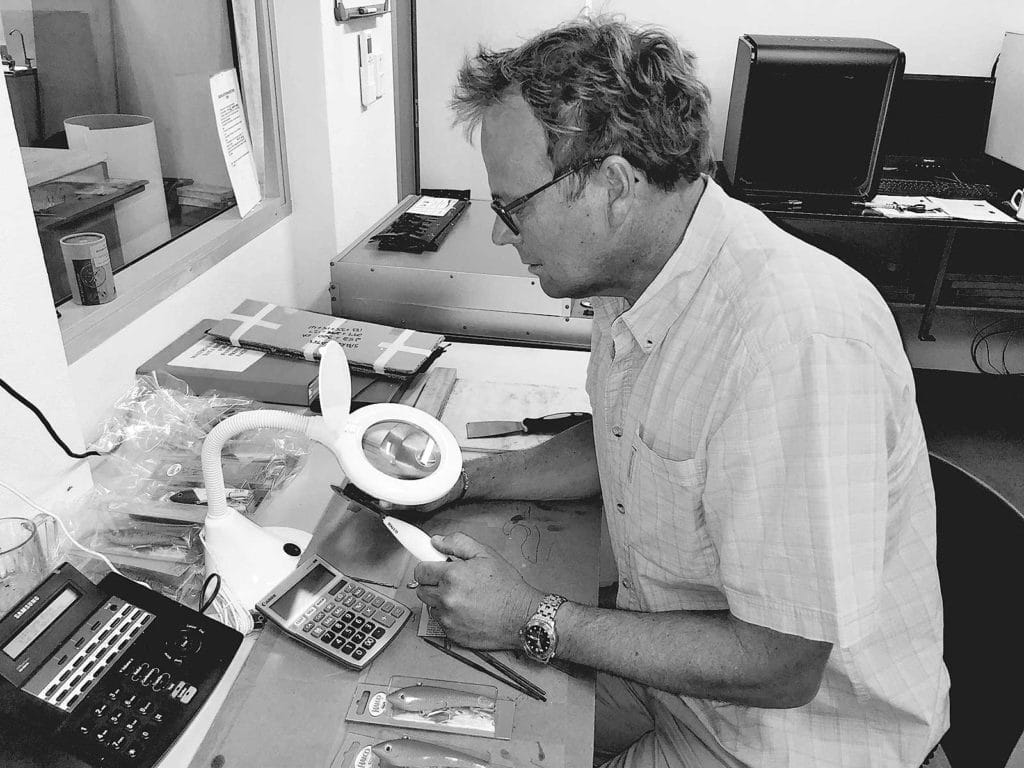

Spend five minutes talking with Dick Fincher of Phase II Lures, and you’ll know this guy is a total fishing fanatic.

Whether you ask him about how a particular plug acts in the water, which hooks are best, or how a lure needs to be weighted, his answers mysteriously turn to the striper that blew up on topwater yesterday, or the bluefish that ripped drag last week. Keep probing, however, and you’ll discover a fascination with lures made of wood that runs just as deep as his enthusiasm for fishing.

Wood fishing lures have, of course, been around for centuries, but making them is labor-intensive. Some of Fincher’s take as much as half an hour to produce — which is not quite as time-efficient as mass-produced injection-molded plastic lures.

“Wood plugs have an action, a buoyancy, that simply can’t be matched by anything made of plastic,” Fincher says. “Wood moves [through water] in ways that can’t be duplicated.”

If anyone should know, it’s Fincher. His lure-making career began when a friend needed help bringing down a cedar tree just over a decade ago in his home base of Westport, Connecticut. He took the wood, made a few plugs that were by his own admission a bit crude, and gave one to his son. “He began catching fish like crazy on it,” Fincher says.

Today he has thousands of handcrafted cedar lures on the water, all across the country. They’ve been attacked by everything from flounder to muskellunge to tarpon.

And these are no simple lures. He first makes a blank, then rough-cuts it, and then carves, sands, drills and paints. Some of his lures involve up to 35 steps in all.

Is the payback worth the process? Money aside, yes. “I love when I get to watch someone catch a fish on my lures,” he says. “There’s nothing better.”